The present survey is provisional and intended to serve as only the merest introduction to a vast and extraordinarily complex field, one that commands broad, ongoing attention. Useful examples and additions are welcome and may be entered in the comments section below the article.[1] An earlier version of this essay was given as a talk in the poetry symposium of “Writing the Rockies,” a conference sponsored by Western State College of Colorado in July 2011. Click on embedded images to enlarge. You may also listen along to the author’s recordings of the essay by using the embedded audio players.

Introduction to Without a Net read by the author

erhaps the single most famous saying about free verse is Robert Frost’s curmudgeonly observation that writing it is like “playing tennis with the net down.” In other words, as an artistic task it fails to challenge; there is, in essence, no game, at least not one worth playing. Although Frost displayed modernist tendencies of some kinds, he never accepted free verse, one of the hallmarks of modernist poetry. It is to be expected that a poet like Frost, whose work embodies the persistence of the accentual-syllabic tradition in English, would be displeased, even disoriented, by the widespread acceptance of free verse in his lifetime. One senses his exasperation as, writing the introduction to a very traditional verse romance—E.A. Robinson’s King Jasper (1935)—Frost catalogs the ruins of modernism.

erhaps the single most famous saying about free verse is Robert Frost’s curmudgeonly observation that writing it is like “playing tennis with the net down.” In other words, as an artistic task it fails to challenge; there is, in essence, no game, at least not one worth playing. Although Frost displayed modernist tendencies of some kinds, he never accepted free verse, one of the hallmarks of modernist poetry. It is to be expected that a poet like Frost, whose work embodies the persistence of the accentual-syllabic tradition in English, would be displeased, even disoriented, by the widespread acceptance of free verse in his lifetime. One senses his exasperation as, writing the introduction to a very traditional verse romance—E.A. Robinson’s King Jasper (1935)—Frost catalogs the ruins of modernism.

The old way to be new no longer served. Science put it into our heads that there must be new ways to be new. Those tried were largely by subtraction—elimination. Poetry, for example, was tried without punctuation. It was tried without capital letters. It was tried without metric frame on which to measure the rhythm. It was tried without any images but those to the eye.

Frost simply could not understand why anyone would bother writing free verse, but still they did, and so a question presented itself with some urgency: after the widespread defection of poets from fixed or inherited forms, how would they go about organizing poems? Poetry still must be written, but how, exactly? Where are the starting points? And what are the goals? What tactics will permit a poet to lend meaningful form to a poem without recourse to established strophic, metrical patterns?

In Missing Measures, Timothy Steele points out that a strong-minded band of free verse pioneers in English—Ford Madox Ford, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot foremost among them—never envisioned free verse as a means by which to abandon form, jettison technique, or turn entirely away from the past. Rather, those involved held that free verse allows the rare genius, one who has internalized centuries of poetic technique, to realize infinite new forms, what some critics have called “discovered forms,” as if they had been there all along, in the Platonic manner, waiting to be revealed. The age called for new techniques, but no one knew quite what the ideal free verse poem might look like. As Jacques Barzun suggested in his essay “The Bugbear of Relativism,”

“Anything goes” has been proclaimed in the fine arts. The absolute freedom of the creator, axiomatic for over a century, has produced masterpieces that demonstrate the value of the ever-new. But since original genius is not given to every artist, much spiritless contriving masquerades as innovation.

Much as poets may like to pose as vatic singers, most still feel obliged to create a persuasive beginning, middle, and ending to a poem as well as engineer a texture or tone that will set it apart from others. One impediment to this ideal is the fact that, as H.T. Kirby-Smith put it in his book The Origins of Free Verse,

we have a naive organicism—frankly egoistic, romantic, and personal—that looks to the nature of the poets and builds on Coleridge’s idea, anticipated by certain eighteenth-century theorists, of organic form. Not only is the poem’s form a natural and concomitant growth with the poem’s substance, but both are projections of the poet.

Stephen Burt, who teaches contemporary poetry at Harvard University, remarked in correspondence with the present author that the subject of pattern in free verse is nothing less than the “largest topic in modern poetics.”

As Paul Fussell memorably put it during the Cold War, “we will want to be aware that free has approximately the status it has in the expression Free World. That is, free, sort of.” Although it may make use of elements of formal prosody—meter that comes and goes like the ladies in “Prufrock,” for instance—most free verse since the 1950s strenuously avoids even the poorest vestiges of Victorian prosody. This is partly due to the fact that, as Barbara Herrnstein Smith wrote in her book Poetic Closure: A Study of How Poems End,

it is difficult to produce or discover a definition of “free verse” that embraces all its acknowledged varieties, that can be stated in positive terms which do not amount merely to a celebration of artistic liberation, and that allows us to distinguish it from, rather than simply oppose it to, other more conventional forms.

Many strategies have emerged to cope with the open field of free verse, several of them before Frost was even born. When moving away from oppositional definitions—free verse is non-metrical, non-strophic—one is confronted with such a vast array of possibilities and examples that it is necessary to summarize and, at times, simplify them for the sake of argument. The possibilities are staggering, but one must begin somehow.

1. Optics

Optics from Without a Net read by the author part 1, Simias to Dylan Thomas

ne obvious method of lending form to free verse is quite literally to shape a poem. Although this is not, strictly speaking, a modern practice, it is one that twentieth-century poets readily adopted and made new. Examples are known broadly as carmina figurata—a term derived from the Renaissance practice of highlighting sacred shapes in red letter type within the standard black letters of a block of printed prose—literally figure poems, or, more recently, concrete poems. The terms are largely interchangeable and may be used to describe poems that rely primarily on shape to provide meaning (as opposed to the more nuanced examples of graphic poems, below).

ne obvious method of lending form to free verse is quite literally to shape a poem. Although this is not, strictly speaking, a modern practice, it is one that twentieth-century poets readily adopted and made new. Examples are known broadly as carmina figurata—a term derived from the Renaissance practice of highlighting sacred shapes in red letter type within the standard black letters of a block of printed prose—literally figure poems, or, more recently, concrete poems. The terms are largely interchangeable and may be used to describe poems that rely primarily on shape to provide meaning (as opposed to the more nuanced examples of graphic poems, below).

Metered poems tend to be fashioned in simple symmetrical patterns, due to the spatial demands of poetic feet. Thus we find wings and axes (they look the same, like hourglasses), diamonds, and plain old big squares. Non-metered poems can take on more supple and intricate patterns because slugs of type may be arrayed as tesserae in a mosaic to fashion just about any silhouette. We find everything from neckties and rodent tails to long-necked swans and banjos.

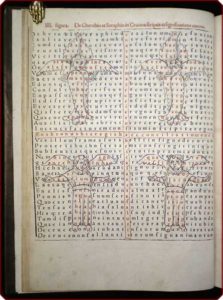

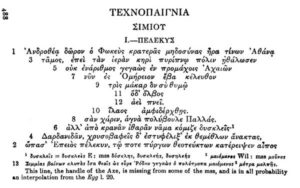

Shaped poems are nearly as ancient as recorded poetry itself. The earliest true figure poems date to the Hellenistic era, in the second and third centuries B.C. The best known examples are Simias’ “Axe,” “Wings,” and “Egg,” alongside Theocritus’s “Pipe” and Dosiadas’ two “Altar” poems. These consisted of dedications composed specifically to be incised on the objects they described. Simias’ “Axe” is made up of choriambic lines that contract and then expand by one foot per line in axe shape, in order to fit on a ceremonial axe—in this case, a votive artifact housed in the temple of Athena and thought to be the instrument with which Epeius constructed the Trojan Horse.

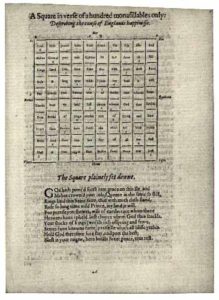

The poem is meant to be read from the outside in (first line / last line, second line / penultimate line, etc.), according to the numbers helpfully provided by J.M. Edmonds in the Loeb Classical Library edition. He perceives a mystical dimension to the cascading lineation of “Axe,” and in fact mathematical and mystical varieties of shaped poetry appear across the centuries. Notable examples include 16th and 17th-century cubic poems that may be read in several directions—such as cruciform poems designed to be read mirror-wise out from their centers. Also known as permutational poems, they describe spiritual labyrinths. For instance, in the late 16th century Henry Lok composed “A square in verse of a hundred monasillables only: Describing the sense of England’s happiness,” dedicated to Queen Elizabeth I. Much like a crossword puzzle, this characteristically permutational poem can be read in a number of different directions.

“A square in verse of a hundred monasillbles only: Describing the sense of England’s happiness” by Henry Lok, 1597

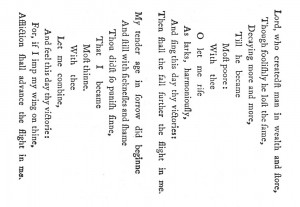

Although wing-shaped poems appeared in several languages in the Renaissance (modeled on early Greek examples), George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” is the shaped devotional poem perhaps most familiar to English-language readers. To accommodate its unusual shape, “Easter Wings” was printed vertically across two facing pages of Herbert’s 1633 volume The Temple: Sacred poems and private ejaculations. Like Simias, Herbert shaves a foot from each line as it advances and then swells the figure out again by adding new feet from the midpoint.

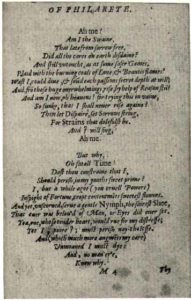

George Wither’s 1622 “Phil’arete’s Lament Faire-Virtue / The Mistresse of Phil’arete” is an example of a diamond-shaped poem.

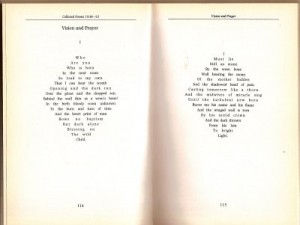

Three and a half centuries later, Dylan Thomas would continue the mystical tradition in this style with his “Vision and Prayer” poems, which alternate between hourglass and diamond formations. Unlike Simias or Herbert, however, Thomas adds and subtracts lone syllables to sculpt his poems.

Optics from Without a Net read by the author part 2, Apollinaire to Ian Hamilton Finlay

Leaping forward several centuries, we discover an explosion of shaped poetry in tandem with Cubism and artistic modernism at large. Notable examples include the Calligrammes of Guillaume Apollinaire, an immediately posthumous 1918 volume that contained a variety of mischievously-shaped poems. Although principally a poet, Apollinaire was deeply immersed in the artistic world of his day, and its influences are plain. He coined the term “orphism” to describe a tendency toward pure abstraction, and he also published an important early essay on Cubism. Apollinaire conveyed these new trends onto the printed page with such poems as “La Cravate et la montre,” truly a typesetter’s nightmare. In Apollinaire, one reads poems about a necktie and a pocket watch formed on the page as those very items. Whether or not they are “pure poetry,” they are pure fun. We encounter little by way of deep meaning or aggressive programmatic posturing.

An earlier example along these lines is Lewis Carroll’s “Long and Sad Tale of the Mouse” from Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland (1865). The mouse’s brief story rhymes as it diminishes in both line length and, eventually, type size, to resemble a mouse’s tail, thus setting up a pun on the world “tale.” It is whimsical and, basically, done for fun. It’s another geometrical flight of whimsy for the Oxonian mathematician.

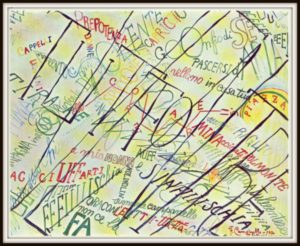

Far more ambitious than Carroll or Apollinaire, Italian Futurists strove to unleash the pure euphoric energy of language, much as Futurist painters had done with color, line, and shape in their highly kinetic, kaleidoscopic canvases. The movement’s founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, declared in his 1909 Futurist Manifesto that the “essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity, and revolt.” This foray included the application of the written word to vibrant works of art, as in Francesco Cangiullo’s 1914 “free words” painting “Parolibere.”

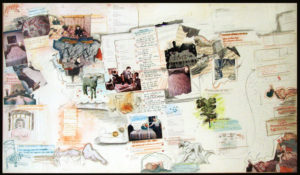

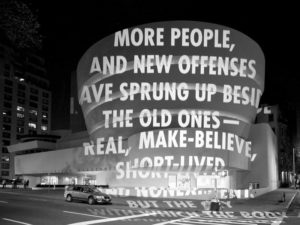

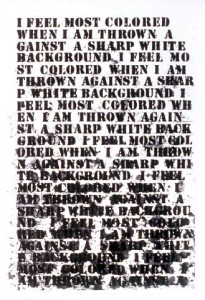

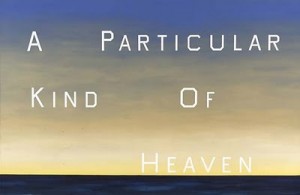

The written word laid siege to the art world, and we see prototypes for later painted poems such as those by New York School members Larry Rivers and Kenneth Koch (“In Bed,” 1982), as well as major text-based contemporary artists like Jenny Holzer (“For the Guggenheim,” 2008), Glenn Ligon (“I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background,” 1990–91), Ed Ruscha (“A Particular Kind of Heaven,” 1983), and Barbara Kruger (“Don’t be a Jerk,” 1996).

To leave the artist’s studio and return once more the print shop, one may contemplate John Hollander’s 1969 collection Types of Shape, in which poems are patterned much like Greek Bucolic figure poems to resemble their subjects, though shorn, in this instance, of regular meter. Perhaps the most widely-anthologized of these is the mirrored “Swan and Shadow,” which mimics the image of a swan and its shadow in the water. When the lines are read across the gulfs that separate them, a call and response pattern emerges: “When [space] soon before its shadow fades / Where [space] here in this shadow of opened eye.”

This icon-making tactic continues to enjoy some popularity today, as in the work of Paul Siegell, who takes the extra step of distributing small printed versions of his shaped poems during readings, to allow audiences to follow along as he performs the spoken component of the poems.

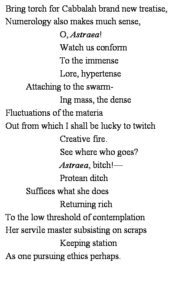

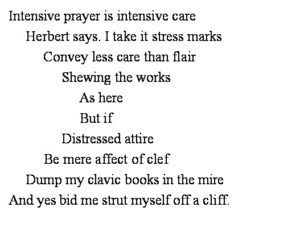

More conventional emblem poems continue to fill shelves as well. This year, Geoffrey Hill’s book Clavics—a word defined in the OED as the “science or alchemy of keys”—features on each page two rhyming, largely iambic nonce stanzas in the shapes of a key and what may be a keyhole (though the latter resembles nothing so much as Herbert’s “Easter Wings”).

Aside from such literal representations, the intoxicating influence of Cubism launched a brand of poetry designed to sport with the visual field while delivering an assortment of ocular signals. One of the best-known, and best-loved, is e.e. cummings’ poem “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r” [“grasshopper” for the uninitiated], which discharges the restless segmented energy of the insect.

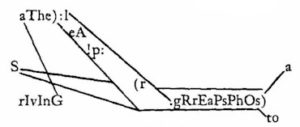

Sam Hynes wrote in 1951 that the “poem is an attempt to deal with words visually, and to create art as a single experience, having spatial, not temporal extension: to force poetry toward a closer kinship with painting and the plastic arts, and away from its kinship with music.” Its remarkable typographical arrangement cannot be read aloud or silently, much less scanned. Swiss critic Max Nänny decodes the “poempicture” as if it were a puzzle and leaves us with an amusing diagram.

from “Iconic Dimensions in Poetry” by Max Nänny, in Richard Waswo (ed.) On Poetry and Poetics, Gunter Narr Verlag, 1985

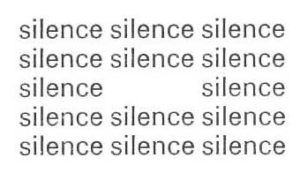

Such early modernist experiments seem carefree when set beside their offspring in the effervescent sphere of concrete poetry, a conspicuously avant-garde international movement that germinated simultaneously in South America and Europe before spreading to the United States. It reached its giddy peak in the 1960s, described by Italian theorist Clodina Gubbiotti as a golden age of visual poetry, when poets and artists attempted to bend and break the written word in every possible direction. The mathematical precision of Renaissance permutational poems was combined with post-Cubist art theory to create a new strain of poem that thrived somewhere between art and literature, soaked in a rich Petri of radical politics. Practitioners assiduously avoided literary allusion or literal shape, stripping letters of meaning, scattering punctuation in non-semantic clusters, erecting colossal letters as landscape art, and even exhibiting carp swimming in a tank with words attached to them as a supreme example of textual instability.

Early German pioneer Eugen Gomringer’s 1954 “Silencio” exhibits concrete poetry’s refusal of narrative. It squats there on the page, striving to become as mute and monumental as a minimalist sculpture. The South American “Noigandres” group combined pop art aesthetics with radical politics. The movement’s name derives from a mysterious Provençal word, whose meaning remains unclear to scholars but which nonetheless appears in Ezra Pound’s Cantos. As Gubbiotti explains, they made “consistent attempts at problematizing the capitalist and imperialist values conveyed by the advertising industry,” as one is meant to understand in Décio Pignatari’s 1957 poem “Beba Coca Cola,” one of the most famous concrete poems. It has been translated as “drink coca cola / drool glue / drink cocaine / drool glue shard / shard glue cesspool.”

Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay went so far as to introduce systems of sculpture, gardening, and landscaping into concrete poetry, attempting to merge the written word with nature itself. His monumental stone incisions recall not only the ceremonial shape poems of the Greeks but also, by sheer scale, the toppled, Ozymandian remains of ancient civilizations, bringing us full circle from Simias’ ancient “Axe.”

2. Graphics

Graphics from Without a Net read by the author part 1, Christopher Smart to Walt Whitman

![]() poem need not assume a literal form, or parade itself as a visual pun, in order to exercise visual qualities that communicate on a level beyond that of language alone. Although shaped, optical poetry existed long before the printing press, graphic poetry is a product of the age of print. Typographical arrangements of letters, lines, and words can send signals, create larger literary structures, divert attention, or even help to announce allusions. A common form of organization in free verse is syntactical parallelism (which often produces long lines referred to by David Rothman as “anaphoric versicles”). Mimicking repetitions common to ancient Hebraic prosody, it establishes a pattern that may continue over the course of a long poem. This method may be used to build a theme, amplify a sensation, or mint ironic juxtapositions, but most importantly it creates form in the absence of meter. One may draw a direct line from English mystical poet Christopher Smart to American poet of the self Walt Whitman (though the good gray poet could not have known of Smart’s “Jubilate Agno”) and, beyond, to Allen Ginsberg and C.K. Williams.

poem need not assume a literal form, or parade itself as a visual pun, in order to exercise visual qualities that communicate on a level beyond that of language alone. Although shaped, optical poetry existed long before the printing press, graphic poetry is a product of the age of print. Typographical arrangements of letters, lines, and words can send signals, create larger literary structures, divert attention, or even help to announce allusions. A common form of organization in free verse is syntactical parallelism (which often produces long lines referred to by David Rothman as “anaphoric versicles”). Mimicking repetitions common to ancient Hebraic prosody, it establishes a pattern that may continue over the course of a long poem. This method may be used to build a theme, amplify a sensation, or mint ironic juxtapositions, but most importantly it creates form in the absence of meter. One may draw a direct line from English mystical poet Christopher Smart to American poet of the self Walt Whitman (though the good gray poet could not have known of Smart’s “Jubilate Agno”) and, beyond, to Allen Ginsberg and C.K. Williams.

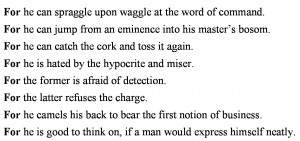

In the middle of the eighteenth century, while committed to a madhouse, Christopher Smart composed a long devotional poem titled Jubilate Agno, “rejoice in the lamb,” not published until 1939. It has gained considerable popularity, largely due to its affectionate and inventive series of addresses to his cat, Jeoffrey.

Each morally instructive line proceeds from the anchoring preposition “for” to describe the admirable traits of the author’s familiar. This quality permits the poem to lunge forward and also lends a pleasing lilt to the otherwise unmatched lines.

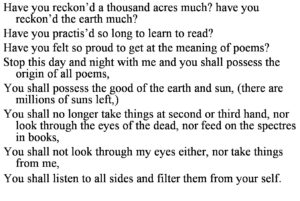

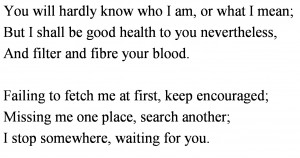

In a first for American poetry, Walt Whitman used syntactic parallelism to organize his long poem “Song of Myself.” As his best biographer Justin Kaplan explains, “to sing the song of himself, his nation, and his century, he had to cut himself loose from conventional themes, stock ornamentation, literary allusions, romance, rhyme—anything that existed for the sake of tradition alone and reflected alien times, alien cultures.” Whitman’s outsized persona could not be contained by the tidy stanzas framed by the more conventional Fireside Poets. Whitman layers lines in direct address to the reader to establish a vivid familiarity.

The first three interrogative lines begin “Have you.” The sequence then pivots on “Stop” in the fourth line and resumes with four imperative lines beginning “You shall.” The appearance of three negatives (“nor”) within these lines creates yet another triple repetition. Whitman uses repetition to create a strong rhetorical drive and sense of intimacy.

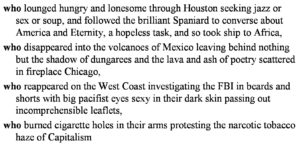

Allen Ginsberg, a poet deeply indebted to this technique, cited both Smart and Whitman as models for his famous 1956 dithyrambic poem Howl.

Ginsberg refers to the “fixed base ‘Who’” in a 1956 letter to Richard Eberhart (he also remarked that the poem is “really built like a brick shithouse”). At the time, Ginsberg’s poetics centered on his notion of a physiological breath line. He commented that “Ideally each line of Howl is a single breath unit. My breath is long—that’s the measure, one physical-mental inspiration of thought contained in the elastic of a breath.” The extraordinarily long lines trigger a head rush and can be held together only by repeating the descriptive “who” did this and “who” did that of the poem’s reportage.

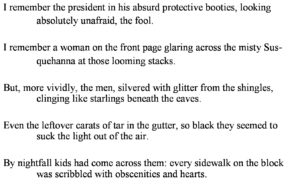

Along the same lines, C.K. Williams is known for composing in passages that, visually, at least, resemble prose paragraphs. Although he relies less on repetition than his predecessors, it is hard to ignore the obvious similarities, as one finds in his terrifying poem “Tar,” written after the Three Mile Island meltdown, in what he described as “those first disquieting, uncertain, / mystifying hours.”

Each extended line is also a complete syntactical unit, ending in a full stop. The repetition of “I remember” sets up a parallel that is amplified and turned with the conjunction “but, more vividly.” It is hard to imagine lines growing any longer without simply becoming small prose-poems.

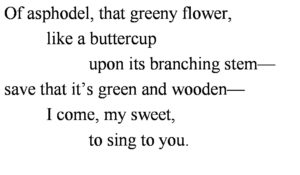

William Carlos Williams patterned his late, long poem “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower” into tumbling indented tercets, a shape that makes the unmetered, unrhymed poem more approachable, though Williams claims he wrote in that fashion only because it helped him to see the poem more clearly despite failing eyesight.

Indented lines in a free-verse stanza represent a vestigial metrical phenomenon. Traditional stanza forms sometimes included dimeter or trimeter lines, known as “bobs,” to bring variety to the regular tetrameter or pentameter lines that surround them.[2] In a similar vein, the quatrain, perhaps the most recognizable stanza form in English, continues its popularity even in free verse, where it often appears more as a “ghost” stanza, in which the visual qualities of the quatrain survive while a standard aural shape—informed by meter and rhyme—has been dropped.

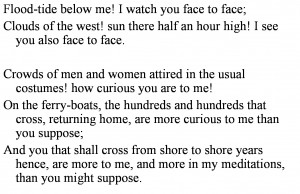

Beyond mere parallelism, line length itself may be used to reinforce larger rhetorical aims, as Paul Fussell observes in the gradual opening up of Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” The speaker’s senses fill with the panoramic view of New York harbor, and the lines enlarge to accommodate the vision, swelling from the opening line of 11 syllables through lines of 18, 23, and eventually 28 syllables.

He accomplishes a similar feat in the slow winding down at the end of Leaves of Grass, after more than 1,300 lines. The lines diminish in length over each of the two famous final verse paragraphs, lending a structural component to the gentle end of what has been called America’s second declaration of independence.

Graphics from Without a Net read by the author part 2, Armitage to Acrostics

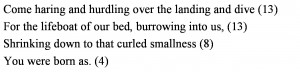

This technique continues to flourish. Simon Armitage’s recent poem “Emily A” replicates the “burrowing” and “shrinking” of a small girl, possibly his daughter, in a syllabically-contracting set of free verse lines:

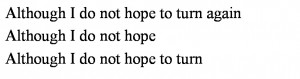

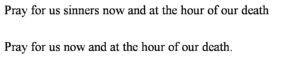

Combining modern typographic techniques with the mystical ingredient of medieval cubic poems, T.S. Eliot arrayed lines in which one or two words are extracted, as in “Ash Wednesday,” which is sometimes referred to as Eliot’s “conversion poem” and which describes a gradual, difficult gain of faith.

Eliot also borrows from the liturgy of the newly-embraced Anglican Book of Common Prayer to create a call-and-response pattern.

One can almost hear a congregation responding to the poet-priest’s solitary appeal in the preceding line.

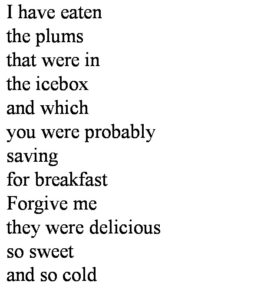

Another technique for forming a free verse poem is drastic enjambment of the kind used by William Carlos Williams in imagist/objectivist poems such as “This is Just to Say.”

Readers are compelled to slow their reading pace and grasp the poem in a mostly arrhythmic manner, as if looking at a painting. Two unpunctuated sentences, announced only by initial capitals, wash over 12 lines. Their simplicity and seeming sincerity, coupled with their fragile transport through a large field of empty white, leave an impression entirely unlike poems of an earlier era. The line breaks are surely not intended as instructions for reading the poem aloud, rather serving as brakes on a car. If the poem were read by Victorian standards, its speaker would sound like a drunken William Shatner.

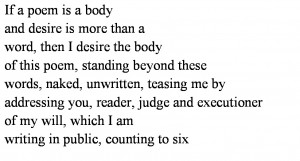

Another method relies on the introduction of specific, arbitrary limits. Bob Perelman is known for sometimes using a fixed number of words per line, as in his poem “A Body” from his 1993 book Virtual Reality, which installs six words, of any syllabic length and sound, per line.

The trouble with parameters such as this is that they only control for one aspect of a line’s creation, ignoring the number of syllables (as in syllabics) or regular rhythm (as in metered poetry). A more sophisticated and successful use of the numerical approach can be found in the work of Navajo poet Bojan Louis, a professional electrician, whose ongoing work-in-progress Currents owes its shape to threes, based on the three basic conductors in an electrician’s work: “a hot, a neutral, and a ground.”

A.R. Ammons typed the book-length poem Tape for the Turn of the Year on adding-machine tape, which severely limits line length over very long stretches (and, as Stephen Burt notes, is also a way for a poet to “try to seem endless”).

The physical limits placed by the edges of the tape result in extreme enjambment reminiscent of William Carlos Williams. English-born Canadian poet Peter Stevens wrote in the Ontario Review that Ammons’ tape technique was “an almost perfect method to allow his . . . organic form to function,” though he was less sanguine when weighing the success of the technique in the later books Sphere: The Form of a Motion and Garbage, at which point the experiment, strained by prolonged use over three full volumes, resulted in a “form [that] seems too arbitrary.”

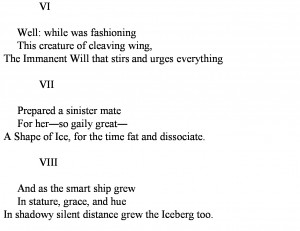

On the far end of the gamut, small, deliberate visual patterns can imply meanings without distracting too much from a verse itself. Thomas Hardy’s 1915 poem “The Convergence of the Twain,”[3] on the sinking of the Titanic, is composed of rhymed tercets, the first two lines of which are inset iambic trimeter built over a longer Alexandrine line, creating the silhouette of both a ship’s superstructure and the visible portion of an iceberg.

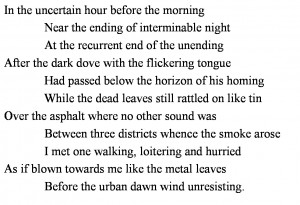

T.S. Eliot uses similar visual cues to summon a Dantean precedent in the ghostly terza rima of the “Little Gidding” portion of The Four Quartets.

In this largely unrhymed passage, the terza-rima-like shape puts the reader in mind of Dante’s Commedia (specifically the Brunetto Latini passage in Canto XV of Dante’s Inferno),[4] allowing Eliot to be led through the bombed streets of the London Blitz by Dante much as the Florentine poet was led by his Imperial Roman predecessor Virgil.

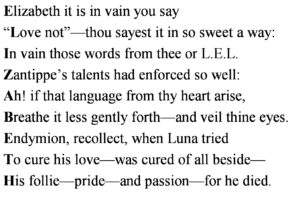

Other graphic techniques include use of acrostic patterns as well as anagrammatic and inverted end-words. Acrostic poems relate loosely to cubic poems, which consisted of full mesostic[5] word squares that could be read in several directions, though acrostics employ only the initial letters of each line to spell out a word. A renowned example is Edgar Allan Poe’s aptly titled “An Acrostic Poem”:

Vertically, the initial letters spell out the poem’s subject, Elizabeth, though one is hard pressed to argue that the trick does much to help an otherwise unremarkable poem. Examples such as this can speak more readily to the crossword expert than to the poet. This is so, not least, because while the presence of vertical spelling might appear clever, or, perhaps merely cute, it makes no impression on the ear and contributes nothing to the poem’s music.

In an anagrammatic rhyme, a poet rearranges the letters of a word to form another. The beauty of this technique is that it can produce wonderful sound effects, as consonance is easily reared from the same group of letters in any order. An excellent example is Richie Hofman’s “Illustration from Parsifal.”

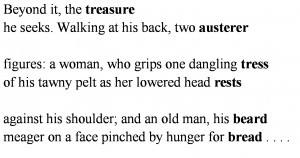

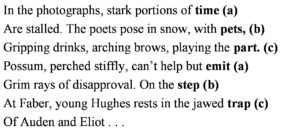

Consonance strengthens and amplifies words that, even rearranged, can sometimes remain half-rhymes. Correspondingly, I make use of inverted end-words in my poem “Photographs above the Desk,”[6] though the results are less musical.

“Time” is matched in the rhyme line by “emit,” “pets” with “step,” and “part” with “trap.” When fully reversed, words rarely rhyme or even work in a consonantal fashion. The use of mirrored words is intended, in this case, to evoke the mirror quality of poets facing each other across generations in a photograph as well as today’s poet contemplating the image of his or her predecessors as if gazing into a mirror. These cases belong to the world of “constrained writing,” in which arbitrary structures and limits, or deletions, are imposed on the language during the act of creation. Further examples include palindrome-poems (poems that read the same back to front), univocalic poetry (limited to a single vowel), and lipograms (in which a letter or selection of letters is disallowed). I am not aware of any poems written with such constraints that also achieve lasting artistic effects, though I remain hopeful that an example may emerge.

3. Acoustics

Acoustics from Without a Net read by the author

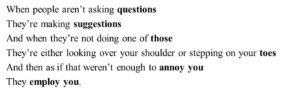

![]() eparting the realm of the visual, one encounters pure sound used to shape poems. David Rothman paraphrases Rousseau’s “Essay on the On the Origins of Language” (“Essai sur l’origine des langues”) in “Verse and the Numerical Imagination” that “for the purest poetry the meaning of verse is the beauty of music, perceived through a pronunciation that requires no diacritical (and therefore graphic) artifice. The metaphorical ‘music’ of verse structure was once indeed music.” He is not implying that the poem as heard takes precedence over or precedes, for that matter, the written poem. But there is an ideal to be found in sound alone. For example, rhyme may lend cohesion to non-metrical lines. Consider Ogden Nash, whose epigrammatic style, even in his longer poems, relies on extraordinarily strong, whole rhymes. Irregularly lineated couplets, dripping with sarcasm, define his style. We wait for big, hammering rhymes as we might anticipate the closing of a musical passage, as in “More About People” (note the double-word rhymes).

eparting the realm of the visual, one encounters pure sound used to shape poems. David Rothman paraphrases Rousseau’s “Essay on the On the Origins of Language” (“Essai sur l’origine des langues”) in “Verse and the Numerical Imagination” that “for the purest poetry the meaning of verse is the beauty of music, perceived through a pronunciation that requires no diacritical (and therefore graphic) artifice. The metaphorical ‘music’ of verse structure was once indeed music.” He is not implying that the poem as heard takes precedence over or precedes, for that matter, the written poem. But there is an ideal to be found in sound alone. For example, rhyme may lend cohesion to non-metrical lines. Consider Ogden Nash, whose epigrammatic style, even in his longer poems, relies on extraordinarily strong, whole rhymes. Irregularly lineated couplets, dripping with sarcasm, define his style. We wait for big, hammering rhymes as we might anticipate the closing of a musical passage, as in “More About People” (note the double-word rhymes).

A contemporary poet who makes use of this technique, one no less sardonic, is Frederick Seidel. He seems to derive perverse pleasure from chaining lines of dramatically different lengths together with chiming, eerily naive rhyme, as in “Poem by the Bridge at Ten-Shin.”

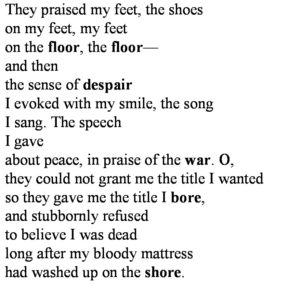

Poets also spread rhyme across a poem to give an impression of isolation or dissolution. Laura Kasischke uses irregular and sparse rhyme to display the gradual unraveling of a speaker in “Miss Congeniality.” Some rhymes fall close together and relate musically, while stray rhymes reside as outliers, visible only to the eye and almost imperceptible, over such cold distances, to the ear. Note the rhyme of floor (repeated), bore, war (internal), shore—as well as the slant-rhyme “despair”—spread out over fully 13 lines.

Kasischke stretches rhyme very nearly beyond its capacity to hold a poem together, but this performance highlights the disintegrating personality of the poem’s central figure, who eventually falls apart altogether and perhaps commits suicide.

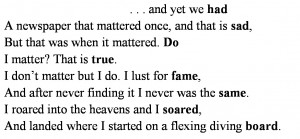

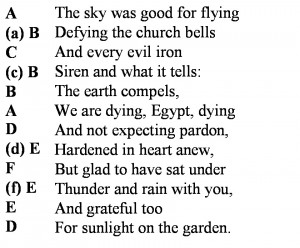

Kay Ryan’s use of free verse rhyme is more muscular and taut, suited to her shorter, epigrammatic style. In a Paris Review interview (Art of Poetry XCVIII), she described what she terms “recombinant rhyme.”[7] Internal rhymes harmonize with end rhymes while working against other unrhymed, enjambed line endings to create palpable tension. A formal predecessor to her technique can be found in “Sunlight on the Garden” by Louis MacNeice.

The tail rhyme in the first and third lines of each stanza is immediately echoed in the first foot of each subsequent line; the first rhyme of the stanza is echoed in the last line; while the second, fourth, and fifth lines share a single tail rhyme. The scheme results in a beautiful poem that captures the anxiety and fading elegance of the 1930s generation on the eve of the Second World War, when, as Auden lamented, “not a word of poetry could have prevented the horrors.”

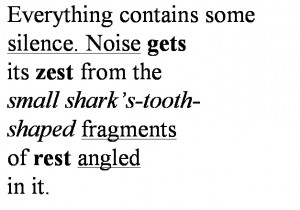

Similarly, Ryan’s recombinant rhyme produces disquiet worthy of Hitchcock. We find the technique used to perfection in a poem like “Shark’s Teeth” from Ryan’s 2005 collection The Niagara River, as the aural contours of the poem grate against its visual ones, causing a sense of jaggedness and unease.

Forget for a moment that the passage itself resembles a shark’s tooth. It is in the kingdom of sound that Ryan works wonders. “Silence” is pressed uncomfortably close to “Noise,” and the two share a delightful sibilance. The further effect of “small shark’s-tooth- / shaped” is to bring the tongue right up against the sharp edge of the teeth when pronounced, mimicking the shark’s bite. “Fragments” are “angled” just as the two words themselves balance against each other sonically, while “gets,” “zest” (one imagines the scraped rind of an orange skin, which might equate to human skin rubbed against prickly shark-skin), and “rest” cut a rhyme series straight through the poem’s center. A magnificently designed acoustic entity, relying not at all on regular rhyme or meter, such a poem is a marvel, and hard to surpass.

4. Irony, Modulated Astraction, and Technology

Irony, Instinct, Modulated Abstraction, and Technology from Without a Net read by the author

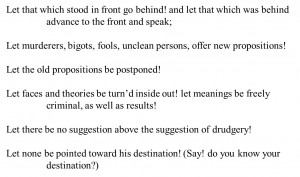

Some organizational techniques applied to free verse could be as easily applied to formal verse, yet their presence is typically more meaningful in a field devoid of set form. Consider Walt Whitman’s “Respondez! Resondez!”, in which each line drips with sarcasm (it is worth noting that it is the only Whitman poem Auden anthologizes in the six-volume 1950 Auden and Pearson Poets of the English Language):

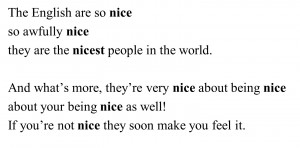

D.H. Lawrence uses repetitive sarcasm as a principle in his short poem “The English are So Nice.” His repetitions would become monotonous if not for their obvious intent. He beats the reader half to death by repeating the words nice, nicer, or nicest no fewer than 17 times in a mere 22 lines. Consider the first six.

This is the literary equivalent of rolling one’s eyes and speaking in exaggerated tones. He wants to make sure the reader knows exactly how he feels about his countrymen, who were not, after all, very nice to him much of the time.

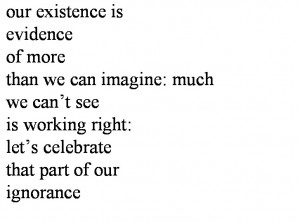

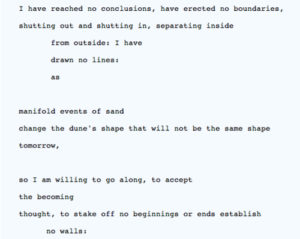

A.R. Ammons’ 1965 poem “Corsons Inlet” dilates between one and 16 syllables per line in order to mimic the contours of both the inlet and the paths of the wandering mind on a long stroll, “thought, to stake off no beginnings or ends establish / no walls.” Formlessness, in this instance, is only a variation of form.

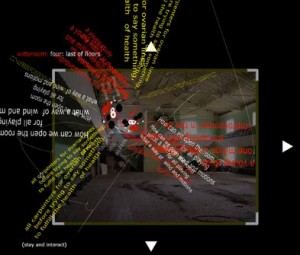

Formlessness may also, at times, assume the guise of a gesture toward aesthetic liberty or be employed as a tool of exploration. While one may be tempted to see a typical poem by John Ashbery, for instance, as gaseous or essentially shapeless, it is this very deflecting technique that lures a final shape from chaos. Ashbery has declared that his “poems have their own form, which is the one that I want, even though other people might not agree that it is there. I feel that there is always a resolution to my poems.” His poems are not the result of chance operations, as are (at times or in part) the poems of John Cage, Jackson Mac Low, Fluxus poets, and their internet-age progeny, Flarf poets. Ashbery’s poems may at times incorporate overheard conversations and found texts,[8] but they are designed, in each case, to generate a specific effect. In a strange sense, he could be said to leave nothing at all to chance. Readers thrill to the unpredictable qualities of the poems, the semantic back-flips, funhouse wordplay, and rhetorical barrel rolls. Ashbery’s poems twist and turn, defying obvious logic and conclusions, varying line length with feverish enjambment, screeching to a halt in unusual places. David Rothman compares this aversion to regularity and measure to the avoidance of tonality in the works of composer Arnold Schoenberg—in other words, “a carefully modulated abstraction.”

A simpler, more common approach to shaping a free verse poem is what I will call the instinctive. A poem’s shape, its length, its sound, are determined not by strict observance of a pre-ordained structure of any kind but instead by the needs of a rhetorical gesture. Once a point is made, an image completed, an emotion displayed, a story told, the poem ends. It is accomplished according to what it tells and shows and not by any outward form. Examples are abundant. Take Sharon Olds’ “Pain I Did Not.”

The shortest line is a mere six syllables, the longest double that number. Internal rhymes, “grate” and “gate,” for instance, and half end-rhymes, “best and “first,” lightly draw lines together while allowing them to flow. It ends much as one might expect a short story to end, just at the moment when enough, but not too much, has been said. The reader registers a conclusion, but it is not patent or easily anticipated. It is organic in a way that Coleridge would not have imagined. “Pain I Did Not” pours along a course of vivid memory, passionate emotion, and a central, governing metaphor, extended to absorb no fewer than seven lines of the poem. This type of poem illustrates the prevailing variety of free-verse poetry over the past few decades; it characterizes a departure from poetry that aspires to the purely aural or visual. This strain is not experimental according to any avant-garde logic, nor is it, strictly speaking, what one might consider traditional (although one could argue that it has become the new tradition in many respects).

Detail from 13th-century illuminated Icelandic Saga manuscript, the Arni Magnusson Manuscript Institute in Reykjavik, Iceland. Photograph by Bob Kristfrom.

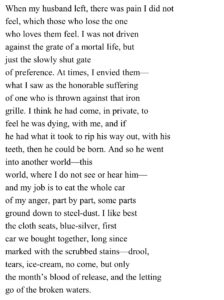

Technology itself, advancing with dizzying swiftness, continues to alter the way poets compose. As Marshall McLuhan observed, “we drive into the future using only our rear view mirror.” Poetry has adjusted to accommodate every major technological transformation related to the word. Before the age of the printing press, when writing surfaces were costly and hard to come by, verse was often written in continuous lines. It thus appeared prose-like, upon first glance, though verse qualities readily surfaced when audited. The introduction of the typewriter changed the way poets as unalike as T.S. Eliot and e.e. cummings composed. Charles O. Hartman wrote in his 1996 book Free Verse: An Essay on Prosody that “typewriters and visually irregular free verse encouraged many poets to experiment with the look of their poems, and to demand a new kind of control over the print-shop.” Access to business machines led to the mimeograph revolution in postmodern poetry in the 1970s.

The internet and home computers have given rise to hypertext and digital poetry, and inaugurated a restless age of sometimes dazzling, sometimes tedious interactive poems that change according to reader input. Earlier this year The New York Times heralded the arrival of Twitter poetry, claiming much “evidence that the literary flowering of Twitter may actually be taking place. The Twitter haiku movement—‘twaiku’ to its initiates—is well under way.”

Thankfully, many fish swim free of the tattered nets I’ve thrown into a very large ocean. There are simply too many examples to cite in a reasonable space. It is impossible to know what bizarre breeds of poem will be unleashed by future technologies, but, barring a wholesale return to traditional verse forms, as well as to the types of publishing technology that reigned from Gutenberg to the age of the smart phone, poems will continue to scatter, reform, and shift shape as long as poets practice their venerable, endlessly variable craft.

Epilogue

Epilogue from Without a Net read by the author

I will end what has become a rather dispassionate survey with something of a personal statement. Of the approaches addressed—optics, graphics, acoustics, and what I lazily admit under the heading of irony, modulated abstraction, or instinct—it is the acoustic that matters most to me, and which I believe essential to good and great poetry alike. I am not referring solely to the fact that spoken and heard poetry—art on the tongue, so to speak—pre-dates written language (some hold to the notion that prehistoric writing systems produced the “numbers” that allow for measure, later meter, in poetry). However, I do feel strongly that a poem must contain a verbal, rhythmic heft or presence in the air (or imagined when read silently). In short, I want to clarify for the record that I find many optical approaches to poetry little more than diversions, at times outright gimmicks, though I allow for mystical elements I am likely unqualified to comment upon. I find some amusing, though rarely, if ever, moving, and I consider them to be more a branch of pictorial art or design than literature. Graphic approaches to poetry, generally more subtle, add novel dimensions to written poems (they are impossible to communicate verbally), thus enriching them, but they are not, finally, important. The acoustic, whether in free verse or in fixed forms, means the most to me. This is, unscientifically speaking, the musical element in poetry. Jon Stallworthy writes in his essay on versification for the Norton Anthology of Poetry (he served as one of the editors for many editions) that a “poem is a composition written for performance by the human voice. What your eye sees on the page is the composer’s verbal score, waiting for your voice to bring it alive as you read it aloud or hear it in your mind’s ear.” This credo is not meant to be absorbed as a precise standard, but it is useful for the practicing poet. Literary art expressed in rhythmic patterns is as old as civilization itself, though such rhythms can take many and varied forms. Assonance, consonance, rhyme, and alliteration furnish the effects of melody and harmony. Words and phrases chime. Even if they cannot be comprehended simultaneously (as with harmony) and do not adhere strictly to pitch (as with melody), the analogy remains worthwhile. A poet with a sophisticated ear will produce more interesting poetry than one who ignores the musical properties of the art in order to simply connect dots and fill spaces.[9] A traditional stanza—even the impish, anticlerical limerick—holds to both an auditory shape and a visual structure. In other words, one could identify a limerick simply by either seeing it or hearing it. Ultimately, both aspects are inherent and vital to the existence of poetic form. Pure sound, as in sound poetry, or heavily acoustic poetry, as in spoken word, stand at one end of a spectrum; on the other end we find shaped poems, with their purely visual effects, crawling into the worm-hole of post-modern art that is concrete poetry. My favorite poems dwell on the acoustic end.[10] Ezra Pound remarked that “poetry atrophies when it gets too far from music.” On this count, at least, I agree with him. You won’t see the music. You must hear it.

[1] I extend gratitude to scholars and editors who helped me shape this essay from earliest ideas to the final version, including Stephen Burt, David Rothman, and Sunil Iyengar. Thanks also to David Yezzi, who provided an apt title.

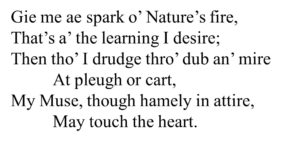

[2] An example is Robert Burns’ “Epistle to John Lapraik, An Old Scottish Bard”:

[3] Critics sometimes cite William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow” to make a similar point.

[4] Additionally, John Drury points out in The Poetry Dictionary that “T.S. Eliot suggests the difficult rhyme scheme merely by alternating masculine and feminine endings.”

[5] Mesostic poems contain words printed vertically down the center of horizontal lines of type, unlike acrostics, which appear at the beginnings of lines.

[6] Sixty Sonnets, Red Hen Press, 2009.

[7] The term is likely derived from cell biology and genetic engineering. Merriam Webster defines recombination as “the formation by the processes of crossing-over and independent assortment of new combinations of genes in progeny that did not occur in the parents.”

[8] Ashbery used a cut-up technique similar to that of William Burroughs when composing his bewildering 1962 poem “The Tennis Court Oath,” though the two appear to have been unaware of each other at the time.

[9] One of the greatest insults one may hurl at a poet to this day is that he or she is “tin-eared.” I hear it bandied about often.

[10] I leave off right around the point that one reaches the likes of G.M. Hopkins, where sound begins to overtake sense altogether:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw fláme;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same [. . . .]

![17 grasshopper[1]](https://www.cprw.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/17-grasshopper1-300x295.png)

Thank you for printing this: it’s one of the most interesting, informative essays on free verse I’ve ever read, and manages to be at once passionate, honest, civil and open-minded on a topic that can be emotionally charged: not an easy combination to achieve. Bravo, Ernest Hilbert!

I have long taken Frost’s maxim to imply that free verse is much, much harder to do well than formal verse. You and I could not possibly have a tennis match worth watching or playing without a net; Djokovic and Nadal just might.

Conversely, free verse is much, much easier to do poorly — for if one can write formal verse, one will at least have something recognizable as a made thing and there will be some music in it, however hackneyed; contrariwise, any free verse not produced by geniuses will not have that music which alone makes poetry bearable.

I very much enjoyed this. Auden’s heterometrics are fascinating: he obviously loves the pattern on the page, but he provides aural effects also. I still find it difficult however to quantify critically those visual effects (I agree with you that they are secondary). Then you have someone like Muldoon who’ll write heterometrics but suppress them visually, pushing all the lines flush left (concealment being a major theme of his). Hecht and Wilbur, et al. What would their poems look like if they were printed without the little indents? Very very hard to say. They would lose something, but what are the exact dimensions and valency of that thing?

Brilliant, painstaking, and erudite, Hilbert’s essay nonetheless saves the best for last, and puts melopoeia in “plain American which cats and dogs can read,” to use a phrase of Marianne Moore, whose work in syllabics also mines the page for optical effect. Yet the reason that poetry in received forms, however loosely employed or adapted to new or “nonce” uses, remains more memorable–more easily “gotten by heart,” as our British and Irish cousins say–is because of the way it engages our “auditory imagination.” The way it becomes “a dance that our bodies remember,” to quote a lecture I heard Jay P. White give many years ago at Vermont College.

Mr. Quinn, thank you for writing. I believe that one dimension of what I term the “bob,” after Paul Fussell, is that it signals, graphically, an alignment with traditional printed poetry (as one finds in my footnoted example from Robert Burns). For Auden and Muldoon to supress the visual component of heterometrics is hardly surprising when one thinks about it. Both writers, their deep traditional qualities in abeyance, strove to be modern in a way that appealed less or little to the other two. Hecht and Wilbur more likely delight(ed) in the visual cues that connected their poems to the visual styles that typesetters once used to demark a heterometric stanza. That’s one dimension. As I suggested, it may be the only one. I invite further comments on the topic. – Ernest Hilbert

A post-script from a recent interview with Richard Tillinghast: “Whenever poems stop being songs they lose something—though not all those I’ve singled out above are songlike. When there is no musicality in poetry, then something vital is lost.”

I wish to join others in congratulating Mr. Hilbert on his excellent survey of poetry, including rhyme, with a title too long to retype! The author shows how poets when faced by the awful void of freedom have, mainly, sought for some organizing principle in their writing, however haphazard. I appreciate the mention of rhyme without meter, which I refer to, in my own writing, as occasional or rambling rhyme. I like the way the essay was organized and presented, with magnifiable text windows. I listened to some of the reading but found that listening interfered with my visual reading and so turned off my speakers. Altogether, one of the best offerings on CPR to date. Thanks.

Pingback: “Without a Net”: Ernest Hilbert on Optic, Graphic, Acoustic, and Other Formations in Free Verse in the Contemporary Poetry Review - E-Verse Radio

“I find many optical approaches to poetry little more than diversions, at times outright gimmicks, though I allow for mystical elements I am likely unqualified to comment upon.”

I couldn’t agree more, Ernest, with the caveat that the comprehension of “mystical elements,” presumably visual, presupposes a certain amount of acquaintance with art/anthropology/spirituality if not mystical experience, and the latter, assuming it were present in the reader, might be pleasant enough to, happily for her, overwhelm whatever the poem had to say. :=?

Ernie,

This is fantastic. I’m going to make it required reading for my AP students. Thank you for it.

I’ve wrestled with the idea of “optical poetry,” going so far as to suggest that it should be a third form of literature (poetry, prose, “optical poetry” as you say).

Do you think it holds up as poetry or would be better viewed on its own? Certainly it can have artistic merits (as any literary form) but sometimes goes beyond (or away from?) what we consider poetry proper. Is that our limitation or the result of a more dire but yet unnamed difference between form?

Ernie, here’s the Trethewey poem where she takes a “palindromic” approach to the arrangement of her lines, the last three stanzas being a complete reversal of the first three.

Myth

I was asleep while you were dying.

It’s as if you slipped through some rift, a hollow

I make between my slumber and my waking,

the Erebus I keep you in, still trying

not to let go. You’ll be dead again tomorrow,

but in dreams you live. So I try taking

you back into morning. Sleep-heavy, turning,

my eyes open, I find you do not follow.

Again and again, this constant forsaking.

Again and again, this constant forsaking:

my eyes open, I find you do not follow.

You back into morning, sleep-heavy, turning.

But in dreams you live. So I try taking,

not to let go. You’ll be dead again tomorrow.

The Erebus I keep you in–still, trying–

I make between my slumber and my waking.

It’s as if you slipped through some rift, a hollow.

I was asleep while you were dying.

~ Natasha Trethewey

When I mention palindromic poetry as a type of constrained writing, I have in mind pure palindromic poetry, which would read word for word the same back to front, across all lines, ideally meeting in the center before flipping back around again. I have found no examples of this style that work well as poems, though many poems exist in this style.

I find Natasha Trethewey’s poem a useful and original use of the “back to front” or “outside-in” approach to writing and a valuable addition to our understanding of ways that free verse poems can be organized. I’m not sure precisely how to describe what she does, but “linear palindromic,” ugly as it sounds, may suffice. Many thanks for sharing with me and CPR’s audience.

After publishing my essay on free verse, I came across this delightful and accurate list of “tricks” or “moves,” largely grammatical, sometimes graphic, used by mainstream contemporary American poets to make their poems “poetic” without recourse to rhyme, meter, or strophic patterns. Thanks to Mike Young and htmlgiant.com. I think this list is very useful, and quite amusing! Click below to read.

http://htmlgiant.com/craft-notes/moves-in-contemporary-poetry/

Here’s a palindrome from my book Wily Apparitions:

Cassandra

grieves

and fears

all remedies

illusion.

Illusion

remedies

all fears

and grieves

Cassandra.

Excellent essay: very informative and useful for poets themselves.

Excellent. This was a great read.

Really love the “This is Just to Say” piece by William Carlos.

Pingback: hinterland poetry | Something Old, Something New – The Return of Letters