As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

Americana by John Updike. Knopf, US $23. 95 pages.

John Updike balances upon, and in many ways defines, the center of the beam in American literature. While maintaining a highly literary elan and readership, he has managed to avoid the obscurity and ostentation associated with “highbrow” authors. Flipping this coin over, one realizes that he also treads the muddier waters of otherwise mundane suburban American iniquities, marital infidelity (consider Rabbit and Bech), drugs and drink (consider Rabbit’s son, Nelson, who put a “whole car dealership up his nose”), the whole cornucopia of vice and folly, without succumbing to the sensationalism of mainstream (read “lowbrow”) authors.

John Updike balances upon, and in many ways defines, the center of the beam in American literature. While maintaining a highly literary elan and readership, he has managed to avoid the obscurity and ostentation associated with “highbrow” authors. Flipping this coin over, one realizes that he also treads the muddier waters of otherwise mundane suburban American iniquities, marital infidelity (consider Rabbit and Bech), drugs and drink (consider Rabbit’s son, Nelson, who put a “whole car dealership up his nose”), the whole cornucopia of vice and folly, without succumbing to the sensationalism of mainstream (read “lowbrow”) authors.

As a poet, Updike is thought of primarily as a practitioner of Light Verse, a term bestowed as often to insult as to categorize a poet, catching up in its loose netting a variety of brightly-colored fish: verse de société, parody, epitaph, clerihew, occasional verse, anything unconcerned with love, beauty, death, formal experimentalism, the stuff (or stuffing as is often the case) of serious poetry (even the designation “verse” is meant to be a bit contemptuous, the yield of poetaster rather than poet). Wit, cleverness, and breezy elegance define the genre, and in these métiers Updike is gifted, to be sure, but he has never been limited to such. Amid his Nashian poems of the past four decades, there were innumerable moments of incredible grace and depth.

For instance, his poem ‘Dog’s Death’, though rarely anthologized, is recognized as that unusual thing, a genuinely sad poem. It brinks at every turn the slope of sentimentality that drops down into the chasm of maudlin corniness, but it manages to hold its footing: “As we teased her with play, blood was filling her skin / And her heart was learning to lie down forever.” It is perhaps one of the rare times that a reader might apply the description “sentimental” without intending harm to poem or poet. There were mock-heroic poems such as ‘Midpoint’ (from the collection Midpoint, 1969), using Miltonic “arguments” as easily as John Dryden and inserting photographs as easily as any postmodern “we-can-fit-one-more-into-the-phone-booth” poet. The poem is, with little question, parodic, but it seems to stretch the limits of Light Verse as it is understood. There were also nostalgic, pensive moments reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s later poems, such as ‘Oxford, Thirty Years After’: “Our cafeteria / is gone, but cast-iron gates and hallowed archways / still say keep out, not yours, all mine beneath / old England’s sky of hurrying gray stones.” It should be remembered that Updike purposely devoted one third of his Collected to the more humorous and weightless poems, in a section headed “Light Verse”. This acknowledges that he does indeed write in such a vein, but it also demands that readers recognize it as only one in his repertoire.

The universal presence of Updike’s Collected Poems 1953-1993 (1995) on bookshelf and at bedside is less evidence of respectable sales than a testament to the ubiquity of Updike as artificer and archaeologist of Americana. Updike’s poetry has never marked a stylistic vanguard. He is a public author, a man who writes to be read, not to be martyred. His poetry is generally seen as an extension of his calling as a novelist, and this should not be taken as a harsh assessment. The same remarkable qualities that frame his fiction are felt in his poems. An au courant eloquence and intelligible image-driven symbolism carry over from his prose, and he never entirely sheds the novelist’s drive toward psychological assessment and coloration (this is equally the case in his criticism and essays, which, like the poetry, are invariably captivating). Rather than emanating from a novelistic Zeusian Swan or Shower of Gold, his poetry can be considered a close cousin, one content to relax in the comfortable light generated by the Rabbit quaternary and The Witches of Eastwick. It is hardly original to describe Updike as an example of that fading breed, the Man of Letters, but it is true. He exists in the stately heritage of Robert Penn Warren and Randall Jarrell, dispatching from his pen criticism, plays, novels, short stories, essays, children’s literature, memoirs, and, of course, poetry.

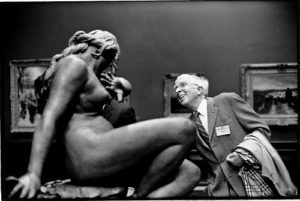

The men, women, and materièl of Americana—Updike’s first book of poems since the appearance of his Collected six years ago—are distributed according to four themes: America as seen by the traveler (the literary road dog, if you will), Updike’s childhood, foreign travel (beyond the realms of America but not of Americana), and an Audenesque homage to the simpler comforts of life. Images dwell in these poems as indications of human desire, and they are shaped to accommodate them: “traveling strangers, numinous, their brisk / estrangement here a mode of social grace” can only be understood as a prelude to “these persons throng / my heart with a rustle of love, of joy.” That they are “numinous” should not be mistaken for an avowal that they (his fellow travelers, dozing in the terminal) are anything other than emotionally-perceived and imaginatively re-conjured considerations of the poet’s idealizing impulse toward harmony in the world. While a John Ruskin (who would not be terribly out of place in Updike’s world) would no doubt raise here the objection of “pathetic fallacy”, the reader knows that the rabbit in Updike would just as easily frisk himself free from such gloomy pronouncements. One imagines the smiling author at a cocktail party counseling “oh, one mustn’t be so hard on the muse, or she won’t call you back.”

Although assembled into groups that can safely be called sequences, each poem in Americana is constructed around its own story or flash of observation, modeled to stand on its own. As is always the case with the effortlessly-published Updike, these poems will be familiar to readers of The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Atlantic Monthly, The American Scholar, The Partisan Review, the standard bearers of the literary ancien-régime of American letters (one will never see Updike in Volt, Salt, LIT, Slope, or any other monosyllabic preserve of twenty- and thirty-something writers, and one suspects that he is quite comfortable with the case). The poems are superlatively comforting. The reader can identify the contents of the plate before him, a rib-eye and buttered roll rather than jellied eel and barbecued grubs. There are poems suffused with genteel but indignant pique, such as ‘The Overhead Rack’:

Why don’t the smug smooth bastards check

their preening polyester wardrobes and

proliferating printouts, sheaf on sheaf,

at the ticket counter, or, better yet,

stay home and attend to their neglected wives

and morose, TV-mesmerized offspring.

There are others proportionately suffused with affection and charm, such as ‘To Two of My Characters’:

And, Essie, did I make it clear enough

just how your face combined the Wilmot cool

precision, the clean Presbyterian cut,

hellbent on election, with the something

soft your mother brought tot he blend, the petals

of her willing to unfold at a touch?

I wanted you to be beautiful, the both of you,

and, here among real flowers, fear I failed.

From the foregoing examples it is clear that the volume is not dedicated to Light Verse. If anything, it should serve to finally dispel such overconfident notions. While recent years have seen several novels and memoirs from writers known principally as poets-Gustaf Sobin’s The Fly-Truffler and Deborah Digges’s The Stardust Lounge spring to mind-it is refreshing to see yet another book of poetry from Updike, who, like many great novelists of the early twentieth century—D.H. Lawrence, Ford Madox Ford, Thomas Hardy—evinces a willingness (and sheer will) to compose in a variety of forms, the poems, like porpoises, no less beautiful or streamlined than the novels, the grand liners, they escort to sea.