As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

Sailing Alone Around the Room: New and Selected Poems by Billy Collins.

Among the many impediments to which contemporary poets much admit, Dana Gioia wrote in his vital essay “Can Poetry Matter?” of notoriously poor sales figures. Whether this was the result or cause of bad behavior was not (and is still not) entirely plain. It is true that some of the English Romantic poets (certainly not the lone genius William Blake) made very real fortunes from their books, fortunes that allowed them to enjoy lives of supreme decadence by the standards of most living at the time. In that age, a book was a luxury item rather than a disposable airline read or stage of a multifarious marketing plan; it cost considerably more, largely due to the binding, and its purchase could be compared roughly to that of a microwave oven or decent futon in our economy. Conversely, literacy was confined to a drastically more narrow band of society than it is in the first world today. Only those who could read could also afford to purchase books, a very cozy market if one is willing to tolerate the overbearing moral attention paid to the printed word.

Among the many impediments to which contemporary poets much admit, Dana Gioia wrote in his vital essay “Can Poetry Matter?” of notoriously poor sales figures. Whether this was the result or cause of bad behavior was not (and is still not) entirely plain. It is true that some of the English Romantic poets (certainly not the lone genius William Blake) made very real fortunes from their books, fortunes that allowed them to enjoy lives of supreme decadence by the standards of most living at the time. In that age, a book was a luxury item rather than a disposable airline read or stage of a multifarious marketing plan; it cost considerably more, largely due to the binding, and its purchase could be compared roughly to that of a microwave oven or decent futon in our economy. Conversely, literacy was confined to a drastically more narrow band of society than it is in the first world today. Only those who could read could also afford to purchase books, a very cozy market if one is willing to tolerate the overbearing moral attention paid to the printed word.

Today, editors at large houses will sometimes take on books of poetry as auxiliary or personal projects. Some, like Adrienne Rich, with W.W. Norton, produce a regular profit. Usually, however, it is the case that poetry lists are show horses. One would never yoke them to draw plow through field. In other words, they are kept. They must be subsidized. If not, publishers look immediately to them when mulling over poor annual returns. A recent example is Oxford University Press, which made the controversial decision to unload its poetry list for financial reasons. Not only did the list fail to make a profit, it was a white elephant. The ensuing clamor produced certain facts both instructional and a little obscene to the public. Jon Stallworthy, the very image of a literary gentleman, pointed out during the fray that such poets as Gerard Manley Hopkins failed to sire a great deal of profit for many years but are now canonical (thus very profitable to the farsighted editor). On the other hand, it became public knowledge that some of the poets on the Oxford Poets series had sold fewer than ten copies of their books. This was embarrassing for all involved.

Unlike the artifact-driven world of visual arts, where speculation and singularity of a given work can drive prices through the most vaulted of ceilings, the poet faces small prospects of making money strictly from poems themselves. It is difficult to imagine a John Wheelwright poem found jammed into an old roll-top desk suddenly fetching millions at Christie’s the way a painting by Martin Johnson Heade could. Poets may sell their papers and notes, most of slight interest to any but the serious biographer, but it is usually the case that the poet has passed on before these seem valuable to libraries and research collections, as was the case with former British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes (unlike its British counterpart, the American Laureateship allows the hope of leaving the post alive). Poetry simply does not sell, and perhaps there is little reason that it should. There are only rare cases in the modern age when any poet gained significant trade. Even collections of essays and cryptic engineering monographs easily outsell most poetry.

Then there is the case of Billy Collins, an American poet who is so fiercely sought by editors that a contract dispute between his publishers made the front page of theNew York Times. His new and selected poems, Sailing Alone Around the Room, has sold over 55,000 copies in hardcover to date (this figure will likely swell nicely as he attends his appointed rounds as Poet Laureate). This is astounding. It is equivalent to a mid-list novelist suddenly selling a million copies. Such success might be expected immediately to draw a confident share of derision from other poets, but Collins has already beaten them there: He has written from the perspective of an envious poet observing a colleague cum antagonist ascending the pantheon of luncheons and Guggenheim checks (‘The Rival Poet’): “In my revenge daydream I am the one / poised on the marble staircase / high above the crowded ballroom.” This is precisely his defense mechanism, self-effacement, and, yes, he has even written about such defense mechanisms, in particular those used by animals in order to avoid being slopped down by larger predators (‘The Butterfly Effect’): “an adaptation technique whereby one species / takes on the appearance / of another less-edible one.” Such mechanisms are now vestigial. He is king of the poetry jungle where popularity and influence are concerned. At the New Yorker‘s “In a Time of Crisis” reading at Cooper Union on October 22nd, 2001, the announcement of his name accumulated the most invigorating round of applause heard for an older poet in downtown New York in some time.

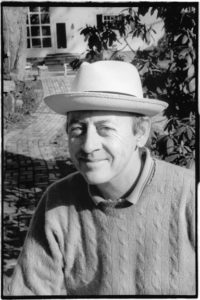

Collins is sixty years old (one tries not to think of the “sixty-year-old smiling public man” of Yeats’s ‘Among School Children’). He has spent (one thinks endured) thirty of those years teaching English composition at Lehman College, in the Bronx, where he is nearly invisible and unknown even as a minor celebrity to students or faculty. He has a six-figure book contract from Random House in his pocket (or wherever he keeps it). He is a tea drinker, a trait readily glimpsed in his poems, which are invariably about himself and the essential aspects of his life. The best way to get at Collins the man is through his poems. This seems passé and shabby as far as critical approaches go, but it will serve. His name bespeaks an avuncular, unassuming, and very American man, in much the way that “William” Collins would bring to mind a Restoration English poet, his calfskin bound King James Bible on candlelit desk. His poems are tidy, both philosophically and anatomically. This combination can be pleasing, in its way, and one enjoys reading through his collections much as one enjoys very well written detective fiction, Dashielle Hammett or Raymond Chandler. He never treads the dark realms that attract most American poets, the clatter of over-alliterated “spoken” poetry or the clutter of the historically over-detailed long poem.

Collins prefers stanza-oriented lyric poems that marshal a broad prose-like diction into a concentrated insight. They do not particularly demand or reward repeated readings. Perhaps this is the cost of popularity. In politics as in art, simplicity and directness are formulas for capturing the attention of crowds. While Harold Bloom, the dear beached blowhard, might insist that the definition of a work of “literature” is that it must excite larger dimensions of emotional reaction upon repeated readings, few will choose to read A la recherche du temps perdu once through much less pull it off the shelf again (if they even have the strength at a later age to wield its heft). Bloom is, however, correct in his assertion. The time and exertion involved might be repulsive to light readers, but it is necessary to get at the center of any complex work of art. His prescription is perfectly suited to the reading of modernist poetry. A poem like David Jones’s In Parenthesis requires several readings before many of its qualities and shapes become available. This prescription also serves as a bridge across the idiomatic distance that separates the modern reader from a poem like John Milton’s Paradise Lost or Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. Repeated readings establish a familiarity that allows ever greater ranges of comprehension and appreciation. This is not true of Collins’s poems. Every bit of meaning is easily wrung out by the attentive reader on the first round.

It is a bit disturbing to enjoy a poem so much the first time that it becomes limp upon a second reading. One of the reasons it seems so appealing the first time is its ease of entry. Then the helium hisses out. The trade off is apparent. Many poems inSailing Alone feel purposely disposable. In the case of a breezy (and greasy) poet like Charles Bukowski, the once and future Poet Laureate of the Los Angeles Low Life, the disposable nature of the poems reflects the disposable nature of the world around him, dive bars, crappy television shows, freeway billboards, boarding houses, anonymous sex, bottle after bottle. Each poem is torn and tossed like a losing ticket at the track. Occasionally there is a winner. Usually, though, the reader skulks away with empty pockets and no babe. This is all fine in its way, as Bukowski drives incessantly at something (though he can not imagine what) through the binges and hangovers, factotum jobs and evictions, up the hills and down, with just enough energy to start back up again. He was writing for his life. He may have been one-dimensional, but he scratched out a dimension to which the reader is drawn again and again, much as his characters are drawn again and again to bar and bottle. But then Bukowski was never in line for a comfortable tenure track job, much less the top poetry post in the nation. The simplicity that enlivens Bukowski’s work is less easily forgiven in Collins’s more classroom-style poems. In either case, it reduces to a simple aesthetic decision on the part of the reader: Urgent gratification or gradual enlightenment. If one selects the former, Bukowski and Collins are the choices of the hour. They might represent the top and bottom of the staircase so far as the official role of the poet is concerned, but they are close in every other sense except that Collins does not share bed bugs or swigs with the late Buk.

As the Roman poets reported on many occasions, fame–however slight it might appear against the glaring stupidity of HBO pop concerts and endless (thus enervating) awards shows–draws both allies and contenders. Among Collins’s admirers is John Updike, a frequently excellent and always prolific author who has been labeled middlebrow. If one risks entering the densely mined fields of the “brow” wars, Collins might also be termed middlebrow, and this is no insult. In fact, it might just save what remains of the brief spark of genuine popularity poetry experienced in the late 1960s. Collins has also been knifed while entering the forum. In the New York Times Book Review, Dwight Gardner compared him to Jerry Seinfeld. While Collins felt that such a barb stung, he might take solace in the thought that Seinfeld’s television program was more than adequately superior to most other programs aired during its reign.

There will probably always be a conflict between obscurantism and populism in American poetry. The more obscure poets can in some cases claim inheritance from modernism. Their poems are toppled columns of a former empire. More reader-friendly poetry has a long tradition in the twentieth century that continued unabated directly beneath the grand experiments of modernism. There are those who still prefer the poetry of Rudyard Kipling to anything written after. If poetry has fallen out of favor with the general public, at least to the extent that it held with poets like Edwin Arlington Robinson or Walt Whitman, it is generally because of its purported difficulty. “I don’t get poetry” is a refrain often asserted even by avid readers. In the conflict between obscurantism and populism, populism would seem the way to the hearts of the many. In England, Iain Sinclair’s Conductors of Chaos anthology set off a chain-reaction of downright phosphorescent responses and gained reasonable sales. Its chafing effect was not unlike those caused annually (and probably intentionally) by the Turner Prize for art. A comparable anthology in America, such as Primary Trouble, edited by Leonard Schwartz, Joseph Donahue, and Edward Foster, failed to rouse much trouble at all. The difference was simply this: in the first case, the intention of the book was to spark debate over a previously “submerged body” of poetry that had (according to Sinclair) been unfairly neglected; in the second, the editors earnestly conceived their anthology as a progressive and accurate depiction of American poetry. It is impossible that a poet like Collins would have appeared in either anthology. Likewise, it is impossible that any of the poets in either anthology could individually (or collectively) have sold as well as Collins. There is no doubt that he will find a place in the more academic Fifth Avenue anthologies such as W.W. Norton’s, but such troves are intended almost wholly for educational purposes. Ease of reading, aesthetic bubbles that pop at a touch, are everything in some quarters, especially in classrooms where basic grammatical units are troubling to affluent twenty-two year olds incubated in the sour light of video games and bad music. Very importantly, it seems that Collins has gained a positive readership outside of such organs as anthologies and juried prizes. He has an audience. This can come as a relief, that poetry is gaining in popularity, or discomfort, that only poetry of a diluted sort is fit for mass consumption.

Whatever else may be said of Collins’s poems, they are never overtly theatrical, ominous, or corny. They are quiet and open. They are representative of a style that is commonly seen in small magazines. He is a competent poet, one easily understood in his own age. This could be a dilemma (strictly in terms of posterity, vita brevis, ars longa) or a virtue (in terms of contemporary influence, hodie mihi, cras tibi). It has been suggested that if American poetry can be said to have a period style it is Ashberian: superficially casual, multivalent, disjunctive, closely allied with theories that drive the visual arts of the age (Henry Darger as much as Helen Frankenthaler or Willem De Kooning). The term “Collinsean” may well become a common term, at least for a time. If one were to pitch Collins to a reader as a Hollywood script is pitched to a producer, it might be a matter of “Ogden Nash meets John Updike, who turns out to be his long-lost son, then runs into a mellowed W. H. Auden, who has just moved in next door to W. D. Snodgrass, who will go on to marry Kenneth Koch, but we can always change that if you don’t like it; we’ll get Garrison Keillor to do the voice over for the ad campaign; you’ll love it, trust me.” This is more than a little flippant, but it is not intended to be at the expense of Collins. These are all worthy predecessors, and Mr. Keillor certainly helped him up the heap of American poetry by featuring him frequently on his Prairie Home Companion.

Collins does not have an especially distinctive style. Invariably a narrator directly addresses the reader. This narrator seems a lot like Collins himself, and the circumstances certainly tally with those of Collins’s life. There are no excursions into dense metaphysical distress or shattering emotional episodes. In his defense, these would seem little more than hollow play-acting if he were to mimic the tones of a Rainer Maria Rilke or Paul Celan. Irony exists, to be sure, but as does a gloss over a completed painting. In other words, it does not saturate the body of the poem. He pokes some fun at himself and others, but he never risks tripping himself up. The poems are for the most part enjoyable, skirting the scarcely perceptible line between art (anguish, emotional growth, intellectual challenge) and entertainment (passive enjoyment, though not to be mistaken for fun, which involves one in its workings). He is a poet of the quotidian, more interested in the household than the transcendent arrangements of religious ecstasy. His poems are humorous, but he has never been in any clear danger of being termed an author of light verse (a challenge John Updike has repeatedly faced in his career as a poet; it might just be that Updike is better at light verse than other kinds). Collins’s poems always maintain a firm center of gravity. They come across as written by a man who grew up in New York’s outer boroughs (Queens). He feels no compulsion to don the tough guy raiments worn by suburban poet-kids weaned on misread (and easily copied) Bukowski. Likewise, he is unwilling to ascend the heights of frescoed ostentation scaled by veterans of private schools and summer trips to the Amalfi coast. He burnishes. He takes an otherwise dull event or object and permits its surfaces to shine. Rather than engaging in identity-building routines, he simply faces his own reality in his own way. Here is a Laz-E-Boy of a poem, typical of the book; it won’t build critical pecs or abs, but if one is determined to be recumbent it beats sleeping on a sunken ratty couch:

I ask them to take a poem

and hold it up to the light

like a color slideor press an ear against its hive.

I say drop a mouse into a poem

and watch him probe his way out,or walk inside the poem’s room

and feel the walls for a light switch.

He is anecdotal, but not in the bizarre, ticklish manner of James Tate. The reader is clearly in command of the idea that many of the occurrences in a Tate poem could not have actually happened to Tate. Again, the matter of transparency comes to the fore. Philip Larkin was a jazz aficionado his entire life, yet one did not encounter jazz drumming in his poems. He kept the jazz in his essays and on the phonograph. There was no need to scan “Sonny Rollins” or hear “John Coltrane” forced into an anapest. Dwight Gardner titled his review ‘Stand Up Poet’, and this appeared at first to be unnecessarily unkind. There is something to the “Stand Up” epithet, though. A small riff on the fear of flying (sans the treasured zipless fuck, which an Ashberian might spin from the metaphorical and literary-pop-historical potentials of the language):

At the gate, I sit in a row of blue seats

with the possible company of my death,

this sprawling miscellany of people–

carry-on bags and paperbacks–that could be gathered in a flash

into a band of pilgrims on the last open road.

Not that I think

if our plane crumpled into a mountainwe would all ascend together,

holding hands like a ring of sky divers,

into a sudden gasp of brightness [. . .]

It is a scene we can all capture instantly, the grim Interzone of the airport waiting area. Remember, though, if a stand-up comedian tells a joke about flying, he will be booed (at least in New York City). One wonders if Collins has any TV Dinner poems hidden in a file somewhere; “you don’t have leftovers, you have reruns, etc., thank you very much.”

The reader will also come across some old chickenbones of poetic diction that catch in the throat, though they are rare in his generally well-served vernacular repast: “over the commotion of trees / into the open vault of the sky” and “sun glinting off the turrets of clouds” need no gloss. They are imported directly from the nineteenth century and would be better served on Antiques Road Show than in a book of poetry. He can be forgiven these few slips, as he is not celebrated as an exceptional stylist. His is a poetry of commentary. It is not reflexive (in a serious way) or process-oriented. This is why it works for so many readers. The vox populi may never absorb the qualities praised in advanced poetry over the past century. Evasion is associated with Bill Clinton fidgeting before his witch-hunters and demanding of them a definition of “is”. Obliqueness brings to mind a C++ manual. Ambiguity is pointless when it comes to engine repair or financial accounting. These tactics smack of corporate lawyers slithering from the yoke of responsibility to commonweal or individual. Why should one be compelled to pay for (or, for that matter, pray for) something he can not see? Again, art, entertainment, commerce, and custom settle into battle for an unenthusiastic mob.

Outside the Coliseum, however, Collins offers a palatable message to occasional readers of poetry: things are not perfect, but they certainly are not as horrid as they might be. There are comforts that are unconnected to rhapsody, discomforts unalloyed with agony. These make up the larger share of life for most Americans, and so his is the voice of everyday America (for what it is worth). Many literary magazines have a house policy (written or tacit) against poetry written about writing poems: No self-portraits (or boardwalk caricatures as they usually turn out). Many of Collins’s poems concern the act of writing or discuss the poems themselves, and they do seem on occasion to be well-wrought coffee mugs if not urns. This might bring one closer to understanding his popularity. He is transparent. He pulls back the curtain to expose the creaky scarecrow of a man working the controls of the thunderous Oz, before whom students are meant to bow. To witness the parturition of a Yeats poem (through what paleographic materials are available) induces bewilderment and some throbbing in the frontal lobes, but Collins makes it a part of the playfulness common to his style, as in ‘Sonnet’:

All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now,

and after this one just a dozen

to launch a little ship on love’s storm-tossed seas,

then only ten more left like rows of beans.

How easily it goes unless you get Elizabethan

and insist the iambic bongos must be played

and rhymes positioned at the end of lines,

one for every station of the cross.

This gambit makes him appear considerably less threatening and possibly quite agile to the casual reader. He is also humble at just the right times. There is no bombast, no Greek goddesses, no cocaine, no wild sex, political outrage, spiritual paroxysm, none of it. This is encouraging because it likely does not belong there. One will not find these items in Robert Frost or Thomas Hardy either. They sold just fine while still engaging future generations with their depth. The question is simply this: will Collins, whose books will eventually be strewn thickly across the country, have the depth to engage future readers or was this depth sacrificed in order to gain popular appeal? Cyril Connolly aptly described poets arguing about modern poetry as jackals snarling at one another over a dried well. For good or ill, if Collins’s popularity and sales continue to grow, and if others rise with him, there might be talk of a rainy season not experienced for quite a long time on the flood plains of American poetry.[/private]