Blind Huber by Nick Flynn. Graywolf Press, 2002; $14.00 (paper), 89 pp.

As Reviewed By: Randall Mann

Nick Flynn, who generated considerable buzz for his first collection, Some Ether, has followed it up with a project book about bees. Blind Huber is a sequence of little monologues (or “extracts,” as he calls them) in the voices of François Huber, an eighteenth-century French beekeeper who, according to the book’s gloss, though blind since childhood conducted experiments for fifty years and “discovered, or re-discovered, much of what is now known about the honeybee”; his lifelong assistant, Burnens; and the drone and worker and queen bees themselves. It’s a curious idea, and one can only admire Flynn’s research and how well-versed he is in the business of beekeeping, yet his complacent language not only fails to complement his ambition–it scarcely declares ambition. The men and the bees drone on and on, disappointingly dull, and all sound almost exactly alike–like Nick Flynn. It’s telling that the most engaging thing about Blind Huber is the gloss at the end that provides the back story.[private]

Flynn’s bees and men are allergic to rich, surprising words and phrases. The talk is of “the frenzied heat of wings” and the hive that “brims with thought” and the queen that’s “a fortune of honey,” honey that “must fall like rain,” “dank” corridors, an “enormous” wind, a “desperate” hush, et cetera. And there’s no shortage of the Poetic, “mountains still / rising from plains, // like music, // only it can’t be heard”; a virgin queen who declares that “I’ll gnaw my / way out, soon, smell // where the other virgins sleep, / trapped // in that perfection forever.” (“Forever,” Nick Flynn’s favorite word, is the last word in three poems.) The author certainly employs some of the minor tics of the avant-garde–one-line stanzas, inscrutably harsh enjambment, white space, words thrown all over the page like litter, titles (with parentheses), rhetorical questions–but at heart he’s a conventional, middle-voiced sentimentalist.

Nick Flynn cannot help himself. A moment of beautiful cruelty, for example, in “Workers (guards)”–“A drone // failed to follow, a young one, / gorging himself on honey, // & ten of us surrounded him, / held his mouth shut”–is followed immediately by the new-age “We are // infinitely more abundant / and we are all the same.” Or “Innocence,” which for the first eight lines reads like something from the Old English, full of lovely directives: “Once fear // subsides, place the hives outside / the kitchen, say a prayer, reach bare- / handed in, tear off a fistful.” But then the final three lines reach for sentiment: “Innocent as cattle, / we whispered, bring us home, // & you brought us home.” Innocent as cattle! Flynn should be found guilty of ruining his own poems. A Nick Flynn poem might begin “When a warrior falls in battle”–but only if it ends with “every pore // now filled with sweetness.”

Flynn turns to François Huber for fourteen of the monologues. At times Huber sounds like a junior-high science teacher (“first // the hive creates a queen, so the queen // can create workers, so the workers can // build the hive”); at other times, a drama queen (“if the sun breaks through / they will find a way out, made // desperate by the hint of distant nectar, // tear a hole like a thought in their wall”). Like a thought? One finds not insight but “just a blind // man staring day after day into loud // air.” When Huber admits that “I no longer know what is outside my mind // & what is in,” one has to believe that Lowell would be maddened by the clumsiness of what passes for confession.

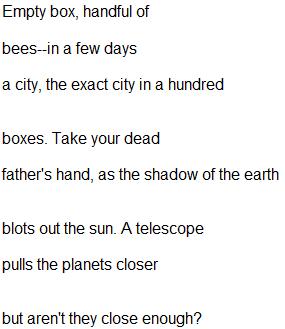

Here, for example, is the complete text of “Blind Huber (xi)”:

I understand, I think, the big idea behind such presentation, the fragmentation and interdependence and compression of language somehow representative of those of the bees and of Burnens and Huber. But bad poetry often is the graveyard of big ideas. Flynn, capable of shockingly good lines such as the Nabokovian “we crawl over // our sisters’ bodies, lick mold // from their eyes,” or “the orchids ruin their sleep,” should be slightly embarrassed by this book. Most of the poems are bored and half-formed, the sequence ultimately pointless, Blind Huber more notebook than Notebook, the line and stanza breaks forced, broken attempts to enjamb some life into what is essentially prose, wingless prose, clipped into lines.[/private]