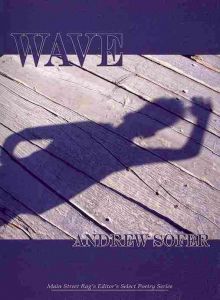

Reviewed: Wave by Andrew Sofer. Main Street Rag Publishing Company, 2010. 63 pages, $14.00

The epigraph to Andrew Sofer’s debut collection of poetry comes from Yehuda Amachai—“And for the sake of remembering / I wear my father’s face over mine”—and it could hardly be more apt. Among other things, the quotation prepares readers for the frequency with which Sofer’s father, who died in his early fifties while the poet was still in grade school, is invoked throughout the book. It raises complex questions of memory and identity, too, especially when one remembers that persona, whence person, originally referred to the masks worn by classical actors. And it allows Sofer, who was born in England but earned his undergraduate degree at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to acknowledge Amachai, that great poet of Jerusalem, as a poetic father.

The epigraph to Andrew Sofer’s debut collection of poetry comes from Yehuda Amachai—“And for the sake of remembering / I wear my father’s face over mine”—and it could hardly be more apt. Among other things, the quotation prepares readers for the frequency with which Sofer’s father, who died in his early fifties while the poet was still in grade school, is invoked throughout the book. It raises complex questions of memory and identity, too, especially when one remembers that persona, whence person, originally referred to the masks worn by classical actors. And it allows Sofer, who was born in England but earned his undergraduate degree at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to acknowledge Amachai, that great poet of Jerusalem, as a poetic father.

If I’ve spent what seems like an inordinate amount of time on Sofer’s choice of epigraph, it’s because it strikes me as typical of the grace and economy of style with which the poet inhabits the various traditions and identities—familial, racial, cultural, literary—to which he’s heir. This sensitivity informs every aspect of the book’s ordering: the poet’s father is both one of the book’s dedicatees and the subject of the last poem. Wave is not only the title, but the last word. There are three sections to the book corresponding, roughly, to childhood, adulthood, and fatherhood. Still, it’s on the strength of the poetry itself that a book ultimately succeeds or fails; we don’t read the Divine Comedy just to admire Dante’s architectonics.

And Wave contains some extraordinarily accomplished poems. One of the best is “Ein Karem,” part of a suite of poems set in Jerusalem, most of them sonnets, that occupies the heart of the book. The title, a note informs us, means “well of the vineyard,” and tradition says that it was to this place, on what is now the edge of Jerusalem, that Mary, pregnant with Jesus, went to see her cousin Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. The angel Gabriel, who foretold both births, and who struck Elizabeth’s husband dumb for doubting the prophecy that she would bear a son, later dictated the Koran to Mohammed.

A lemon tree stands in my yard. Its fruit

by rights is mine. Except the old stone house

I love, which smells of sandalwood and mice,

was Arab—so each dusk the children loot.

Witness the game: when I see them I shout,

when they hear me they run, and in a trice

vanish like sunlight in the olive trees,

leaving their curse behind. It’s not about

lemons at all, of course, but who owes what

to whom. Once near this village an angel spoke,

struck mute the doubting priest whose son was born.

Whose language must we speak to pay the debt?

I raise the children’s crooked stick and shake

lemon after lemon from silent thorns.

The situation the poem describes, while presumably quite literal,alludes to one of the most famous passages in Western literature, from Augustine’s Confessions:

A pear tree there was near our vineyard, laden with fruit, tempting neither for colour nor taste. To shake and rob this, some lewd young fellows of us went, late one night (having according to our pestilent custom prolonged our sports in the streets till then), and took huge loads, not for our eating, but to fling to the very hogs, having only tasted them. And this, but to do what we liked only, because it was misliked.

Those pesky kids and their pestilent customs! The children steal lemons each dusk—you can see them holding those small suns in the gathering darkness—ostensibly because they regard the fruit as rightfully theirs. How do we know this, though? Have they told the narrator this? Have his neighbors? Does he simply assume it, prompted by a sense of inherited guilt? The explanation Augustine might offer of the children’s behavior—they do wrong in order to enjoy their wrongdoing—and the explanation to which the speaker seems inclined—something like Auden’s “Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return” –don’t so much cancel each other out as wrestle for dominance, with the outcome undecided.

The prosodic flourishes in “Ein Karem,” like the multiplicity of meanings that the line break lends to “shake,” to take just one example, are evidence their author is a master craftsman. And really, the first thing one notices on opening (dipping into?) Wave is Sofer’s preference for, and considerable skill with, traditional poetic forms. There are sonnets in abundance (one of which is also a shaped poem), blank verse, haiku, a ghazal, and a poem in a stanza form borrowed from Larkin’s “Faith Healing.” He has a particular preference for repeating forms, favoring us with a villanelle, a sestina, two pantoums, even a double rondeau, the last of these a genuine, if alas unexcerptable, tour de force, “Old City,” again set in Jerusalem.

In “Mea She’Arim” another sonnet, and one that falls at the book’s exact midpoint, the poet addresses his father, saying “Three thousand miles away I’m haunted by /your absence, like the coda to a poem / missing some key phrase just out of reach.” But “Just out of reach” is, in a sense, the key phrase here. Allude and elude share a root, the one pointing beyond the utterance at hand, the other beyond the hand’s, or mind’s, grasp. That sense of the difficult to parse relationship between presence and absence, past and presence, text and context, self and other, is what gives Sofer’s work, quiet though it is, much of its charge. Allusion is not a literary strategy or technique for him, so much as a mode of being.

I’ve referenced Auden, and Sofer himself points to Amachai, but among near contemporaries in English, his chief poetic kinship would seem to be with James Merrill. There’s the preoccupation with memory and with a family past seen, sometimes darkly, through a Freudian lens, the devotion to traditional poetic forms, and, not least, the penchant for puns. The book’s title being a case in point. Waves—ocean waves, light waves, radio waves, television waves—are all means of transmitting energy and information from one point to another. But a wave is also a gesture, of course, either of greeting or farewell. When we’re told as children to wave, isn’t it usually because we, or someone else, is leaving, because we’re saying goodbye?

He’s not always so subtle as that, however. Look at “Renting a Tux”:

Off the cuff, I wonder how many men,

bit players grooming for the major part,

have squeezed their frames to fit the shape I’m in.Buttonholed by bores year after year,

we parcel out our lives in cummerbunds.

Surely it pays to purchase what we rent?And yet how comforting to follow suit,

to wear our hearts on someone else’s sleeve

and, made to measure, dance in borrowed time.

Granted, there are some real groaners here, but then, a Jewish comedian dressed in a tux making bad jokes is himself the inheritor of a long tradition. He’d kill ‘em in the Catskills.

Of course, the occasion par excellence for puns is, of course, sex (“Off the cuff, I wonder how many men”!), and in “Her Key” Sofer brings all his syntactical and prosodic skill to bear on expressing (pressing out) what doesn’t want to be said:

Not bothering about you, except not

to lose you or forget what you were for,

I let you tarnish on a copper ring,

rust into unfamiliar peaks and valleys,

give up the spark that raced from lock to palm

each time the tumblers fell like sorcery.I kept you in my pocket as a charm.

At night you were a magic key, decoding

strangers’ voices, cries behind her door.

The blade turned in my mind sharper than thought

of what no longer opened at my touch.

Your living silver, fading by degrees,

caught in my throat like curdled mercury.

I shut you in a drawer to hide how much.

The first two lines, which read at first as though they might be addressed to the “her” rather than to“her key,” are brilliantly tortured. Notice how the first, in particular, almost unsays itself. The poem is charged—that “spark”—with sexuality, even if it is kept, like the former beloved, at a distance. What’s said invokes what’s not said—“what no longer opened at my touch”; “rust into” rather than “thrust into.” The comparison of the key in question to the key to a chastity belt, made explicitly, might render the speaker comical or monstrous or both. Left implicit it serves to deepen the poem by suggesting the pathetic, perverse, very uncontemporary motivations we shy away from confiding even to ourselves.

Sofer’s conviction that every detail should carry meaning (“No things but in ideas,” Merrill said, reversing Williams’ famous dictum) sometimes gets him into trouble, as in “Boomerang”:

I threw the boomerang in such a way

That it would sail beyond our tidy lawn

Then double back into my waiting palm.Instead I watch my new toy slice the air

And catch my mother just above the eye

As if it meant to cut her down to size.

So far, so pretty darn good. A primal situation and, given the association of the boomerang with Australia, one that the poet likely means us to see as aboriginal, and thereby to catch the echo (another returning back) of Newman’s description of the expulsion from Paradise as “the aboriginal calamity.” (A church near my place of work recently had as its motto of the month, “Love, like a boomerang, always returns.” Either the denomination in question has a darker worldview than I’ve given them credit for, or they’ve overlooked the boomerang’s original function as a hunting tool and weapon.) In its final stanza, though, the poem falters:

I couldn’t make her understand that chance

Sometimes takes matter into its own hands ,

That aimlessness, as well as rage, can blind.

I can see that we’re meant to read in the speaker’s denial of responsibility an allusion to a conflict between mother and child that lies outside the bounds of the poem proper, which may itself be figured in the “tidy lawn” that the text makes on the white page. Ultimately, though, the interpretation that the poet offers in the final stanza strikes me as more willful than laconic, his concern for economy of gesture having rendered him, however briefly, heavy handed.

Earlier I referred to Sofer’s double rondeau as unexcerptable, and I notice that throughout this review I’ve generally cited complete poems rather than individual lines or even stanzas. Here and there one comes across startlingly beautiful phrases as in “Landing,” where the speaker, looking down from an incoming flight, sees a khamsin (a hot desert wind) “scything tufts of grass.” In nearly every case, though, a given phrase or line depends for its effect upon the poem to which it in turn contributes. And of course, given the care with which Sofer has ordered Wave, each poem will in turn remind the reader of, and draw energy from, its fellows elsewhere in the book.

This is all to the good. It’s even a kind of ideal. I will admit, though, that I did wish there were more moments of real roughness or rawness in the book, more lines and phrases that called attention to themselves by their sheer excess of energy, as I think they do in “Her Key.” Maybe I’m being unreasonable in wishing that Sofer would occasionally be a little less reasonable, a bit less measured. Maybe, having just spent some time reading Ted Hughes’s letters, I’m feeling uncharacteristically atavistic.

I’m probably also asking something of Wave that would have been contrary to the spirit of the book. After all, Sofer begins his debut—and every publication, every debut in particular, has a “Hey Ma (or Pa) look at me!” quality to it —with what in several senses is a gesture of self-effacement: “And for the sake of remembering / I wear my father’s face over mine.” The book that Sofer goes on to give us, with its deft investigations of the ways in which we owe ourselves, all that we are, to others, is more than enough for now. And I look forward to the next one.