The editors of the CPR wish to thank our readers for their comments, and letters, on the subject of “poetry readings.” Our very short and sarcastic list created a tiff among a number of “the touchy tribe” who seemed to take offense at the notion that all contemporary poetry readings are not wonderfully entertaining events.

The editors of the CPR wish to thank our readers for their comments, and letters, on the subject of “poetry readings.” Our very short and sarcastic list created a tiff among a number of “the touchy tribe” who seemed to take offense at the notion that all contemporary poetry readings are not wonderfully entertaining events.

Some poetasters seemed wounded by the thought that if you can’t recite your verse it’s probably because you can’t remember your verse. An even more outrageous suggestion seemed to be that if you can’t remember your verse, it’s very likely that your audience won’t remember your verse either.

The editors of the CPR considered these remarks to be near-syllogisms, admirably clear and obvious, but then we know that poets are rarely swayed by logical appeals (or given much to bothering with Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, for that matter).

So, we would like to expand our original remarks.

1) To recite your verse, it is necessary to remember your verse from memory, without the aid of notes. To read your verse is to rely, in some fashion, on notes. Reading your verse could theoretically make no substantive difference—in terms of sound— on the performance of the poem, as opposed to reciting it. This statement could be true of recorded audio performances, for example, devoid of a live audience.

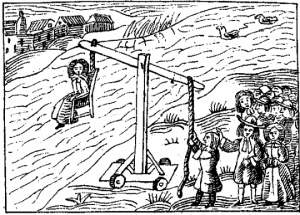

2) Still, reading your verse has an impact in terms of the performance of your poems before a live audience, and that impact is negative. The poet reciting his verse can make use of the actor’s craft—not least of which are gesture and expressiveness—to perform the poem dramatically. By comparison, the poet reading his verse is a humble creature in front of an audience: eyes down on the page, body behind a lectern, mouth in front of a microphone. The poet-reader presents his audience with nothing in terms of his presence (or “visual impact”) but only as a disembodied voice to be heard—much like a school teacher’s lecture. Therein lies a fatal flaw: the audience has come, not to be taught, but entertained. This kind of “poetry reading” is thus an absurdity: the non-performance of verse by a poet in front of a live audience. The poet who can only read his work should, ipso facto, not be in front of an audience, ever. (Those who would challenge this point must also be able to argue that audiences should prefer the dress rehearsal of a staged play to its opening night.)

3) Therefore, the decline of any general interest (or general audience) for the so-called “poetry reading” coincides with the decline of poetry as a recited and dramatically performed art. This strikes us as an historical fact. The more our contemporary poets read their verse, the fewer audience members they will inevitably attract. (Editor’s note: reading to a roomful of other poetasters at AWP does not invalidate our point.)

4) The poet who recites his verse should dramatically perform it. This is not an arguable point: these dramatic performances of Dylan Thomas or Sylvia Plath or Yeats or Tennyson or Pound with his drums should convince even the most hard-hearted. How the poet should dramatically perform his verse is a matter of taste. Though it’s easy today to disparage the more artificial and “stagey” performance of these great poets, it’s best to remember that they had an audience to entertain.

Today, our poets compose their verse mostly for the eye and not the ear. Much of it is not even intended to be read (or recited) out loud at all. It’s “paper poetry” – which accounts for more than 99% of what is written in America. Perhaps it’s not fair to assert that most poets today don’t want to recite their poetry, but rather that they can’t. (Have you ever tried to memorize several hundred lines of free verse?)

The point of rhyme and meter—the purpose of all prosody—is ultimately mnemonic. From that standpoint, most of what our contemporary poets write is not (even technically) memorable. That is, perhaps, the most powerful unintended consequence of the vers libre movement.

Our final conclusion is a commonplace and a warning: the fate of so many American poets who have forgotten to study prosody is to be forgotten themselves.

Read Ernest Hilbert’s fine essay on famous poets performing their work:

Intro: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet/

Auden: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-1/

Jarrell: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-2/

Plath: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-3/

Bishop: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-4/

Ashbery: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-5/

Merrill: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-5-2/

Five Female Poets: https://www.cprw.com/the-voice-of-the-poet-part-7/

As a poet who writes with the sound of a poem, a line, a phrase very much in mind, I agree with much of what you say. However, I still do read my poems in front of an audience. I approach it more as readers’ theatre, which makes use of scripts but in a somewhat stylized way. this is another possibility poets have available, one which I would encourage. A reading is a performance, whether you have the poem in front of you or not. It is a form of entertainment, and poets, while we are giving a reading (or a recital) should remember we’re entertainers. (cue music and out).

By this logic, no prose would qualify as “memorable.” That is obviously false. Therefore the proposition made above that only metrical rhyming verse is memorable is false.

Why poets don’t distribute copies of what they’re reading, so the rest of us can follow along, is a great mystery to me. It would also take so much off their shoulders as performers.

And let’s mention the introductions at poetry readings – which are at least as painful! At my alma mater (a HUGE university!), the department secretary would call the reading to order, then a faculty member would introduce someone who was both an amazing poet and an outstanding exemplar of humanity, who would then introduce the even more astounding poet who was going to read his or her poetry! Then the second poet would spend an eternity thanking and praising everyone, and parrying all that praise!

I have to wonder, why is poetry so embarrassing?! National poetry month (ugh!) is an agony to no end, especially when your friends know that you’re into this thing called poetry!

You pose an unreal dichotomy: reading is dull / recitation is interesting. Clearly that is overstated. Some readings are dull, some painful, some fascinating. Much depends on the reader. Like all public speakers, readers of poetry must learn how to make eye contact with their audience, how to keep their voices alive and natural-sounding; in addition they must remain observant of meter and line-endings. But doing these things does not require abandoning the page altogether. And I’m not sure I want to encourage “gesture and expressiveness” in readers. Expressiveness maybe, within limits, but spare me the gestures that might accompany “Downward, to darkness, on extended wings.” Good readings are a rarity, I agree, but they do occur and they needn’t always be ex tempore.

My childhood memory of those two old guys in the balcony tells me they were a lot better with the one-liners than whoever actually wrote this piece. Worse, it’s a sequel, and, in the way of bad sequels, is unfortunately longer than the original. You really didn’t need to enlarge on it. Small points enlarged upon are still small points.

Of course, poets don’t need to perform their poetry to make a great impact on their audience. I’m sure the author or authors know this, but I didn’t find this defense to be any lighter or funnier than the first article.

I think of the readings of A.R. Ammons, who read his own poems as if he were just re-entering the process of his own thought and discovery, like he was meeting an old friend and found out that hey, he still liked that person after all. It was watching Archie’s mind, his enjoyment of his own work, of language, and reliving his wonder at the world that had helped generate that work.

Far more entertaining than to see an actor “perform” those poems from memory. It would be even more horrifying if that actor was the author!

If “lighter” in this title means funny, both attempts at addressing the subject have missed the mark (hint: lines like “ipso facto” and “those who would challenge this point must…” have never tended to bring the house down at improv joints); if “lighter” means “not to be taken seriously,” then I would reckon the sequel as successful as the first. I look forward to the performance of this piece as a downloadable file, or ringtone, even. Perhaps its unbearable lightness might really shine in that format.

Pingback: Night Is Nothing But Night | Whimsy Speaks

I read some, recite some… I have some set pieces to play with the poetry reading format… but I always want to try something new with an audience and with myself… I really like the embarrassingness of poetry readings as the poster above says. I cringe at the introductions and the offensive justifications people give for their work, but I also think that if you’re playing poetically with the usually unexamined themes of life or the imagination then you really are teasing away a bit of social normality in terms of language and etiquette, so I think embarassingness can actually mean, sometimes, something quite positive.

Also, I really really disagree with the assumption that the most important thing is that a poem be memorable. I want to write forgettable poetry. I think that something that is cleverly written is awkward and evolving and that the experience of it, is not just a repeatable jingle but a shaping experience… I’d like someone to remember the experience of a poetry performance not necessarily the poem, even if it is the poem that shapes it all it might be someone’s own thoughts that they remember, or a mindset shift that they don’t even recall occuring…

Hooray for unremembered poems!

(and my spelling, grammar and made up words x x)

I love how often eye contact is coming up in both of these posts’ comments. And lines amounting to “don’t move, hardly speak, and for goodness’ sake watch how much you intonate”.

Point #2 uses an unsound argument when it says: “The poet who can only read his work should, ipso facto, not be in front of an audience, ever. (Those who would challenge this point must also be able to argue that audiences should prefer the dress rehearsal of a staged play to its opening night.)” This argument could only be sound on the assumption that a poetry reading is always a dramatic performance. But surely, all poetry is not dramatic writing. Is there no distinction in kind between, for example, Shakespeare’s dramatic verse and Shakespeare’s sonnets? After all, most poets do not consider themselves to be writing dramatic verse when they write lyrical or narrative poems. Lyrical poems are often written in one’s own voice, as a record of one’s own thoughts and feelings. Narrative poems often have as much, if not more, in common with prose than with dramatic writing. So do these poems become dramas as soon as we speak them aloud? Hardly. Poets have been reading their lyrical and narrative poems to friends (and to anyone who would listen) ever since they started writing the things down. So, it is difficult to see why we “must” recite all of these poems as if we are playing a dramatic role. What drama? Where are the other characters? What is the setting? Who brought the costumes? Usually, we are just ourselves trying to share some words with others. Recite them if you want to, or just read.

Pingback: “Why We Still Hate Poetry Readings” | Voice Alpha

Maybe some of us are too old to remember, or because our poems have gone through so many versions and revisions that we have to have some way to remember where and when we are in the moment of our performance. I know performers who use their written manuscripts like a jazz players chart, i.e. they riff off the writing, changing words to fit the occasion of the performance. All kinds of ideas work into a performance. I remember reading at a campus once, and knowing what time it was that the bell tower would begin to chime. I read a poem about bells and the audience was amazed at the “coincidental” distant sounds underscoring my performance. I am always impressed when a poet has memorized their poetry, especially if they have memorized more than one poem. Still, no one expects and orchestra to perform without sheet music. Or is it all about the dance?