I teach Hardy every other year in my “Modern British Poetry“ course at Wells College, and this year I decided to use “The Darkling Thrush” to introduce his work to students, many of whom had not read him before. As I looked particularly closely at the poem in preparation for the class—and then, later, during the class in the very act of talking about it—I was struck anew by the astonishing care with which it was put together, and how even the smallest details fell beautifully into place, so as to form a seamless whole that is both moving in itself as a poem and conveniently representative of Hardy’s subject-matter, formal practices, voice, and vision.

I teach Hardy every other year in my “Modern British Poetry“ course at Wells College, and this year I decided to use “The Darkling Thrush” to introduce his work to students, many of whom had not read him before. As I looked particularly closely at the poem in preparation for the class—and then, later, during the class in the very act of talking about it—I was struck anew by the astonishing care with which it was put together, and how even the smallest details fell beautifully into place, so as to form a seamless whole that is both moving in itself as a poem and conveniently representative of Hardy’s subject-matter, formal practices, voice, and vision.

First, the imagery. We all know how Hardy makes use of landscape to convey emotion—”Neutral Tones” leaps to mind—but note how the bleak, cold, barren winter scene is immediately conveyed by the strength of the capitalized “Frost” and “Winter’s,” which is in turn further strengthened by those “dregs” which make “desolate” the diminishing light of the fading sun (personified as well as “the eye of day”). The precisely drab phrase “spectre-gray” is complemented by the verb “haunted” in line 7, and carried over into the explicit—and grotesque—imagery of death that pervades the entire second stanza: the landscape itself is “the Century’s corpse” leaning out of its coffin. And note how “outleant” picks up on the “I leant” at the beginning of the poem. The sky is a “crypt,” the wind is a “death-lament,” the “pulse” (one thinks of blood but also, because of “germ” and “birth,” of germination and procreation), that “ancient pulse” of nature has dried up, and we come to “spirit” again, harking back to “spectre-gray” and “haunted.” Only this time the speaker, who acknowledges he is “fervourless,” suggests that “every” other spirit on earth shares his depleted and desiccated state. A low point has been reached, but things are about to alter dramatically for the better.

Before they do, let’s backtrack for a moment to the imagery in the second half of stanza one. Lines 5 and 6 are remarkable, and remarkably Hardyesque, for the economy and richness of their literal and figurative language. “Tangled bine-stems” is visually what the speaker, leaning on the “coppice gate” (that is, a gate leading to a small wood or thicket), would see, but the phrase metaphorically communicates complexity, a “tangle” that would be hard to negotiate and get oneself through and past. The powerful verb “scored” means “mark,” “incise,” or “cut”—Housman used it equally memorably in 1896 in “Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff”: “Out of a stem that scored the hand/I wrung it in a weary land.”— but here these stems that cut across and into the sky metamorphose instantly into “strings of broken lyres”: in the very act of imagining them as capable of making music the poet already sees them as snapped and hence useless for that purpose. (As a side note I’d like to add that modern readers are likely to recall Frost’s lines about Mary from “The Death Of The Hired Man”:

Part of a moon was falling down the west,

Dragging the whole sky with it to the hills.

Its light poured softly in her lap. She saw it

And spread her apron to it. She put out her hand

Among the harp-like morning-glory strings,

Taut with the dew from garden bed to eaves,

As if she played unheard some tenderness

That wrought on him beside her in the night.

One can’t help but wonder whether Frost was thinking of Hardy’s two lines.)

But let’s proceed, from where we left off, at the nadir of hopelessness. Everything is bleak, freezing, desolate, dried-up, and fervourless, if not actually dead. There is no possibility of music. Structurally (one thinks, always, of Hardy, the architect), this is exactly midway through the poem.

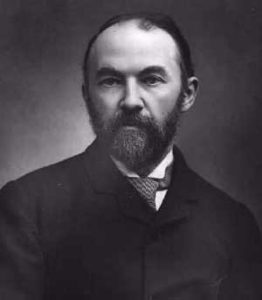

Suddenly, as if out of nowhere and beyond all expectation, music bursts forth, and it originates from those very “bine-stems” that “scored the sky/Like strings of broken lyres.” Nor is it just any music. It’s a “full-hearted evensong” of unlimited joy, pouring out of a bird whose description, as every savvy reader notes with pleasure, bears an unmistakable resemblance to the sixty-year-old Hardy himself: “An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,/In blast-beruffled plume.” This tiny doppelgänger has “chosen”—the word seems significant— to “fling his soul/Upon the growing gloom.” It is worth noting that nothing in the physical environment of the poem has changed. Not only is that pervasive gloom still present. It is even “growing.”

Before moving on to the final stanza, let’s pause just a moment to consider birds in Hardy. I want to mention three, two of which also appear in winter poems. There is that other thrush Hardy admonishes for keeping him conscious of the world’s misery in “The Reminder”:

While I watch the Christmas blaze

Paint the room with ruddy rays,

Something makes my vision glide

To the frosty scene outside.There, to reach a rotting berry,

Toils a thrush,—constrained to very

Dregs of food by sharp distress,

Taking such with thankfulness.Why, O starving bird, when I

One day’s joy would justify,

And put misery out of view,

Do you make me notice you!

There is the sparrow, who makes a decidedly comic appearance in “Snow in the Suburbs”:

A sparrow enters the tree,

Whereon immediately

A snow-lump thrice his own slight size

Descends on him and showers his head and eyes

And overturns him,

And near inurns him,

And lights on a nether twig, when its brush

Starts off a volley of other lodging lumps with a rush.

And there is, of course, “The Blinded Bird,” who is “divine” because he sings “zestfully” and does not blame those who have cruelly condemned him to “Eternal dark.”

So, back to “The Darkling Thrush,” I want to go out on a limb (slightly) in my reading of the final stanza. One of the aspects of Hardy I most admire is his apparent openness to at least the possibility of various alternative answers to the Big Questions. Yes, he is rightly renowned for his pessimism, and yes, he is generally regarded as among the gloomiest of writers. Still, he himself characterized his poems as “questionings” and “explorations of reality.” Many of his poems express a lack of resolution regarding the ultimate nature of reality, a provisional and even an improvisational quality, as if he is never quite willing to completely shut the door on some sort of hope, however faint or farfetched.

In the concluding stanza of “The Darkling Thrush,” there is certainly nothing in the least definite to pin any hope on, even if one allows that just conceivably the bird does indeed know something we ourselves don’t and can’t. But consider that the bird’s “ecstatic sound” is characterized as “evensong,” which is a liturgical part of the Anglican service, and then look at the use of the word “carolings,” with its close association with Christmas, which occurred just the week before. Then there is the reference to “terrestrial things,” which calls forth the thought of their opposite, “celestial” or “heavenly” things, also essential to the narrative of the Christmas season. This brings us finally to “blessed Hope,” which, joined with the other apparent Christmas references, certainly could suggest the Christ child himself and therefore the ultimate promise of Christmas and Christianity. This language seems too specifically referential and clear-cut not to have been intentional, and yet we know Hardy was not a believing Christian. So, is this an instance of one of Hardy’s “explorations of reality”? Has he provisionally appropriated for the dramatic occasion of this poem a recognition that, whatever he himself might believe, for some the “truths” of Christianity could be valid? Are we dealing here, in other words, with a Christian thrush? To me, that seems completely consistent with his willingness to entertain the thought, in many of his poems, that there may be “more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of” in our restless and unending metaphysical inquiries.

A small bonus came to me in the course of writing this talk. The following little poem, which I’ll conclude with, simply popped into my head.

FROM HARDY’S NOTEBOOK

Heard a bird

Loudly voicing

(though absurd)

Great RejoicingPeered about

Wretched Season!

Left without

Learning reason

coppice gate is one made of coppiced wood – doug