Reviewed: Broetry by Brian McGackin. Quirk Books, 2011. $12.95

Reviewed: Broetry by Brian McGackin. Quirk Books, 2011. $12.95

Broetry’s title jumps into a spot your mind didn’t know was there. Sure, you know “bros” and you know “poetry,” and it somehow seems more than natural for a book called Broetry to appear in your hands. And when it does appear, the first thing you notice is that, unlike nearly every other publication of poetry, Broetry is a real book. It’s a nicely sized (5×7.5) hardback with a beautifully embossed cover, a refreshing aesthetic relief from the common flimsy, perfect-bound books of poetry that must litter some unlucky remainder store.

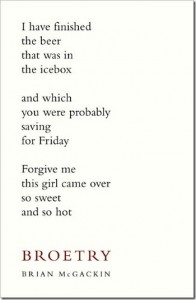

The cover includes a poem that riffs on William Carlos Williams:

I have finished

the beer

that was in

the icebox

. . .

forgive me

this girl came over

A riff that, perhaps unintentionally, bares the subtext of Williams’ original poem. In a move not out of step for Quirk Books, publishers of Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, Broetry refreshes several old chestnuts, mixing them in with its “literary chili cheeseburgers.”

Broetry, proper, begins with the section “High School to Hangovers,” leading off with “Lying in a Sleeping Bag in Nicole Sanchez’s Basement, Prom Night 2003,” which, like several of the poems in Broetry is notable for its name and not much else. The next poem, “Move In,” “has to get better, right?” Well, sort of. It is certainly a better poem than the previous one but it mostly serves to introduce the ditherings (“right?”) and parentheticals “(almost, no)” that infect too much of Broetry. With two weak introductory works, one is almost concerned that Broetry shoots its wad on the cover.

The collection does rise, however, with McGackin’s willingness to play with form first shown in “Not Another Teen Movie,” a cento built from film titles: “The End of the Affair/The Last Kiss. Memento.” In “Close,” “But No,” and “Cigar,” Broetry delves into every schoolboy’s favorite form, haiku, giving us a triptych about the displeasure of smoking ladies which, for Broetry, seems a bit too politically correct but just misogynistic enough. Later sonnets, such as “When Patrick Stewart Rules the World” are quite good and make points, “Caesar couldn’t blame them, either,/yet stayed to fight on in their stead,” that, like the cover poem, are more profound that one expects of “a book called Broetry.”

I went to Future Rome and found

that rebels resurrected Caesar.

Antony they left in ground;

Cleopatra in a freezer.I toured the city at my leisure—

almost everyone had fled—

Caesar couldn’t blame them, either,

yet stayed to fight on in their stead.He rose against the man who led

the Federation so despised.

The walls of New Vatican bled;

too many pilots met demise;but none could long deter the rise

of he who helmed the Enterprise.

Along with the “Patrick Stewart” poem, Broetry is stacked with references to pop culture, from “Now I Assume That Everyone Named Harry Is a Wizard” and “Whorecrux” to “The Guttenberg Bible” (that’s Steve) and “For Mama Celeste.” While some of these poems rely on puns (“Whorecrux” begins “I have halved my heart seven times”) they, like Broetry, can rise above the reader’s humble expectations.

Broetry’s biggest debt to previous and popular culture, however, is retreading other poems—, as its cover does, in the vein of Weird Al Yankovic. Frost gets two treatments, with “Stopping by Wawa on a Snowy Evening” (“We’ve only got two racks of beer/and one bottle of Everclear”) and “The Road Unable to Be Taken Because I’m Trapped Behind a Line of Dudes in Stormtrooper Armor Who Feel the Need to Take Pictures with Every Girl They See Wearing a Slave Leia Outfit,” another poem eclipsed by its title. Whitman appears in “O Captain! My Captain America!,” regarding the controversial decision to kill off Captain America, at least maybe (“—fuck/I think he’s back again.”). With his witty titles that often run to a heavy hand, McGackin shows us he is no T.S. Eliot but he might be the 21st Century’s answer to Ogden Nash, a sort of I-wish-I-were manly Dorothy Parker. In a world where some folks forget that light verse doesn’t stop with Shel Silverstein, Broetry’s wit can be downright refreshing.

The section “Sophmoronic” contains “Golden Grahams,” an unimpressive prose paean to a Saturday morning ritual: the speaker can “choose whatever cereal I damn well please” now that he’s an adult. Like any protest of an adult justifying their childish desires, “Golden Grahams” falls flat as a prose poem, simply checking the “I’ve done every form” box for McGackin. The discomfort mounts with the desperation of “Haikougar”:

Ann Coulter is a

right-wing conservative nut

but I’d still do her.

And comes to an end with the blissfully creepy “Ode to Taylor Swift,” with the great country-and-western line: “you’re still/the reason for the teardrops on my laptop.” These poems, especially, along with others in Broetry are “aided” by illustrations from Lars Leetaru (though they fall short of the bar set by one Stevie Smith).

“Girls, Girls, Graduation” then graduates itself from fantasy relationships to real ones; the book’s strongest emotional section starts with the delightful, devastating, and funny “Yes, I Cheated On You,” one of the few poems I have sought to read out loud to my friends, literature-minded or not, knowing they’ll find the bathroom-as-Pandarus as amusing as I do:

Yes, I Cheated On You

Is that what you wanted to hear?

Because deep down you know that

it’s true, right? Clearly I’m unfaithful.No, I didn’t cheat on you, dipshit,

but I will if you keep it up. Stop

looking for signs that aren’tthere—sexts and e-mails, late night

phone calls—excuses to be unhappy.

If I wanted to fuck somebody elseI’d dump your ass. Where do you

suppose I would find the time to

cheat on you? The fourteen hoursa week we do not spend together

perhaps? Or maybe when you’re

in the bathroom? Yeah, that hasto be it: I can’t wait for you to

go to the bathroom so I can sneak

off and fuck my other girlfriend.If only you had a smaller bladder,

I could cheat on you more often.

“Truth or Dare” asks questions like “How many guys have you really slept with” that no one wants to know, while “You and Me and the Absurd Amount of Baggage You Brought into This Relationship Makes Three” is another poem whose title says it all. In “Finals” and “Graduation,” however, McGackin deftly combines the end of college with the “effects of long-term exposure to/ridicule and constant nagging” and the end of love.

What do you get when you multiply a

selfish young adult who refuses to grow up with

someone too much like himself?

. . .

So we’re probably gonna break up, right?I think we should, although I’m terrible

at making decisions. . .

Broetry’s flyover section is “Extreme Poverty is the New Poverty,” more notable for the typo in “Part-Time Job Search” (“log on, you’re life’s a mess”) than any of its verse. In “Twenty-Five To Life,” the poem improves, teasing words with “a healthy, romantic blow” in “Former Future Lover” and playing games in “Do You Believe in Magic,” a nerdgasm that makes me yearn for my faded purple Crown Royal bag.

Broetry’s flyover section is “Extreme Poverty is the New Poverty,” more notable for the typo in “Part-Time Job Search” (“log on, you’re life’s a mess”) than any of its verse. In “Twenty-Five To Life,” the poem improves, teasing words with “a healthy, romantic blow” in “Former Future Lover” and playing games in “Do You Believe in Magic,” a nerdgasm that makes me yearn for my faded purple Crown Royal bag.

After these poems, Broetry finally turns outward, looking at the speaker’s brother in “And You’ll Be Way Cooler in College,” which holds Broetry’s unofficial motto: “Life sucks./There’s not much you can do.” Broetry should then skip to the end with “Impact” but doesn’t. In their effort to make a “big enough” book of poetry (128 pp), the McGackin and folks at Quirk let too much through the net.

“Impact,” aptly, has the most power of Broetry’s poems within its thematic confines; it is no wonder it’s blurbed on the back: “I go to spend/money, because it is Sunday, it is fall, it is football.” This bro statement should be served as a welcome closing, a masculine antidote to so much metro flailing. Instead, Broetry ends with “Quarter-Life Crisis,” which “all sounds kinda/boring anyway,” a post-modern meta-dismissal of “a book called Broetry,” that serves no purpose other than as a pathetic hedging against criticism; we get it, Broetry doesn’t take itself seriously; it’s what we love about it, not a point that needs to be hammered home, as if the speaker needed to or could pull off Puck’s closing soliloquy.

In spite of its shortcomings (or, the speaker might argue, because of them), Broetry is a success. Its jocular, self-deprecating narrator is a welcome respite to the too too solid speakers one finds today. No, Broetry doesn’t take itself seriously—it’s neither out to change the world nor to gain McGackin tenure—and that’s what makes it so irrepressibly enjoyable. It’s poetry for the sake of a good time, interspersed with the inevitable touch of the “bottle flu” that comes with partying so hard. I guarantee you’ll laugh—and when was the last time a book of poetry could promise that? Most importantly, Broetry is one of the few books of poetry I’ve ever read that I felt compelled to share not only with poets and readers of poetry, but with that set of folks who happily say “I hate poetry,” and that, more than any other aspect of McGackin’s work, is a triumph.

I enjoyed read this review. I think I got just enough of the book to sense that although I don’t want it, I’m glad that it exists. It’s quite fun to have a reader-friendly poetry again. Thank you for the excellent review.

Does the CPR or G.M. Palmer have a mailing address?

[email protected]

My email address is linked to on my CPR bio page.

I wanted to leave the comment ‘your poetry is broeful’ for Mr McGackin but I dont mind a few of the ones listed…

Pingback: Too Cool for School: G. M. Palmer on Broetry | Poetry Chain